This Echo Chamber Life

by

SJ Townend

previous next

Our Love Is

The Most Eloquent

Here to Stay

of Energies

This Echo Chamber Life

by

SJ Townend

previous

Our Love Is

Here to Stay

next

The Most Eloquent

of Energies

This Echo Chamber Life

by

SJ Townend

previous next

Our Love Is

The Most Eloquent

Here to Stay

of Energies

previous

Our Love Is

Here to Stay

next

The Most Eloquent

of Energies

This Echo Chamber Life

by SJ Townend

This Echo Chamber Life

by SJ Townend

The city in which she had grown up had not been kind to her and the doctor had recommended sea air; something about salt, ultraviolet light, coastal life, the brush on skin of a far-travelled breeze. If she were to stay where she was—with her mother, in the city—her mother said she would most likely unravel at the seams, become devoured, masticated and spat out, and ultimately, be at risk of dissociating entirely.

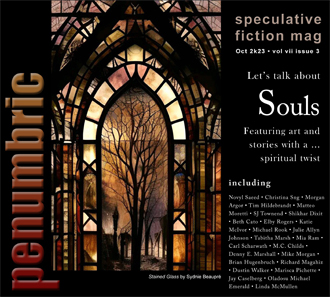

So, after several viewings, she decided to take the first room she’d been shown—isn’t this always the way?—the room in the two-bed property which overlooked the sea, because, as a little girl, she’d always dreamt of living by the sea. And the doctor had been somewhat insistent. And from this point forth, she, the one who signed the contract, shall be referred to as ‘THE FLATMATE’ and the two-bed property overlooking the sea as ‘THE FLAT’.

She, THE FLATMATE, was not sure if it was the doctor who wished her away or the ocean which beckoned her or, perhaps, the prospect of sharing with another girl, who could become, perhaps, a friend, but signing on the dotted line had felt like the correct thing to do. She was not sure of much though. It was as if the situation was out of her hands, out of her control, as if the gravity of the expanse of dark water had taken over.

* * *

“Green or taupe?” the girl who lived in the other room, who shall be referred to as ‘Lil’, asked.

“Either,” the Flatmate replied. “Both look amazing. Wish I had your figure. You could be a model.”

The same conversation rolled out every Friday evening, the pair two-thirds through a bottle of Cheap White. Same Cheap White, same flimflam, blether, unidirectional compliments, the specific date only distinguished by the slight differences in both of the girls’ nearly-outfits. The evening could almost have been a tape-recording set on a timed loop.

Both laughed at the appropriate moments always instigated by Lil, but they laughed in a different way to one another. The Flatmate’s laugh came out overeager, too ripe, a little too loud. Her whole face honked like a goose. Lil’s well-rehearsed laugh came out from only her lips; didn’t want her caramel foundation to crease, didn’t want to dislodge an eyelash. The rest of her face remained Botox-still.

“I’ll wear the taupe. Goes with my new boots,” Lil said more to herself than to the Flatmate.

Even the morning after the night before, Lil was an easy ten, and if she were to come back to the flat with the Flatmate after a night out with the Flatmate, the following morning, Lil would still be sparkling. She’d rise from her silk sheets as polished as a fancy pearl. In comparison, the Flatmate would rise groggy, crumpled, and smudged, as if recently dug up. But in comparison, Lil shone even without make-up. Lil never had bed-head or bad skin or cellulite, and the Flatmate would make prescriptive comments, deliver lip service, would say things like: “Lil, you’d look good in a bin bag.”

The Flatmate—at the start of the night only, and only in the right light at a push—was a seven; a seven who fell to a five point five when stood in the shade of Lil.

The Flatmate was ready to go, so she slid on her sandals, perched on the sofa, and watched Lil carry out her elaborate rituals. Fifteen long minutes passed. The Flatmate finished off the wine and Lil anchored on and tied up her knee-high, lace-up boots, the ones with the five-inch heels.

“Do you think it’s going to rain?” Lil asked and teetered, all sexual stick insect, over to the mantelpiece to pout at her own reflection in the mirror above the fireplace. “I don’t want to get my hair wet.”

“Rain? In June? I doubt it,” the Flatmate replied. Her eyes on her hands, her hands writhing about in her lap, unsure of what to do with themselves, how to rest, how to be, now the wine was drunk. She gawked upward at Lil’s reflection, wished she looked more like Lil. The Flatmate stared hard in the mirror and pretended Lil’s reflection was her own, belonged to her. The only thing more beautiful to see than Lil, is the sea, she thought, and through the far window, to which her eyes flit for less than a moment, she could also see the sea.

The Flatmate sat up straighter, drew her shoulders back, sucked her stomach in. Perhaps in time, the flatmate thought, some of her beauty may rub off on me. But the Flatmate was unsure if, when her thoughts referred to ‘her’, her thoughts had meant the sea, or if her thoughts had meant Lil. Both were things of beauty, but one evoked a feeling of calm, the other, a feeling of resentment. It was the first time she’d lived away from home.

They stepped outside, one after the other, the Flatmate a few paces behind Lil, and set off for the bus stop. The Flatmate looked at the cracks and the gum stuck on the pavement and fiddled with her chafing bra straps and fumbled in her bag for loose change between old sweet wrappers and hair clips and Lil’s stuff which Lil had asked her to carry for her so Lil didn’t have to ‘ruin her own outfit with a bag’. Lil glided along. The Flatmate noted how Lil glided along, observed how a ten moved her arms, cat-walked her legs. She moves with the grace of a swan, the Flatmate thought and tried to emulate her. She made a clumsy shadow; a shadow with unattainable aspiration, a shadow with a lake of fire and jealousy burning in the pit of its shape-shifting stomach.

An ominous rumble cracked from an opening in the sky someplace before the bus stop and after the off-licence Lil had stopped outside of to check her own reflection again in the storefront glass.

“Oh. It appears it might rain,” the Flatmate said and dipped her eyes like half-beamed headlights. “Sorry.”

Lil, a ten, threw the Flatmate—a seven, but a six when wet—dagger-eyes, as if to suggest the situation with the weather was, in fact, somehow the Flatmate’s fault.

The pair broke into a canter, both keen to miss the prospective deluge, and it was when both girls were within a stone’s throw from the number 5 bus stop that a razor clam fell from a cloud. It clipped Lil’s arm on its way down.

They looked at the bivalve on the ground, then looked across it to each other, one’s body language the mirror image of the other’s, centred by the punctuation of a sea mollusc. How odd, the Flatmate thought, although not entirely unimaginable, what with our proximity to the coast. The flatmate had heard of stranger things falling from the sky: frogs, golf balls, roof tiles, impromptu tornadoes of debris.

But not in England. Not on a Friday night out on the town.

The Flatmate wondered if she should stoop and collect the shell, return it to the sea. To take the shell to the sea, to throw it back in, to sit and stare at the sea—these were the things she felt she might want to do. The Flatmate felt drawn to the shell like the shell had been drawn to the surface of the Earth, as if with the force of Jupiter’s pull.

But Lil insisted on nightclubbing each weekend. And, like most actions over time, repetition leads to the formation of a habit. And the Flatmate was not one for confrontation.

“Shit. That hurt,” said Lil. “I’m bleeding.” She clamped her left arm with her right hand to try to stem the flow of her own blood. The Flatmate pulled out a crumpled tissue from her bag and passed it to Lil. Lil turned her nose up at the offering but then, perhaps on realising she had no other choice, for no one else on foot was within sight, accepted it. Lil took to dabbing at the clean slice in her arm the shell had made. It was as if the part of her arm which had no name, the side-spot between the wrist and the elbow, the flank of long-boned flesh, had become undone by a straight, red zipper.

With gusto, Lil kicked the shell. They watched the knife of nature spin and skitter away and along the pavement, saw it pinball against a post and come to a standstill some way off ahead.

Another voluble clack came from the heavens and more crustaceans and hard things from the sea started to fall. “Quick, run for shelter,” the Flatmate yelled and the Flatmate in her flat shoes ran towards the shelter of the bus stop. But Lil, ten, almost an impossible eleven in her too-tall heels, in a state of panic, took a tumble down. Down she fell like the shells from the skyline, down. Down.

God or the troposphere dropped everything else it was holding all at once. A cacophony of marine blades, calcium carbonate sharps, scallops, piddocks, oyster warfare, and rock-hard whelks pounded onto the pavement. Lil, twisted ankle, lay moaning on the ground, unable to flee the shower. Pain. Slicing. Shellfish. Storm.

The Flatmate charged forwards until she reached the bus stop. There, she turned back to look at the state of Lil, a smaller version of Lil now, who lay on the pavement someway off in the distance, or, perhaps, in the past. The Flatmate pondered should I run back and help? She could see the bus in the opposite direction, also small, but larger than Lil, and growing larger. The bus, caught between lighter traffic, edged closer towards its stop, towards the flatmate who stood safe and sheltered. Be a shame to miss it, the Flatmate thought. Next one’s not for half an hour.

Without Lil at the club, the Flatmate thought and stared at her own arms, I’ll be an eight. Maybe an eight point five if the UV lighting which makes my freckles pop too hard is switched off—

The flatmate stroked the unnamed area of her own arm in the same place where on Lil’s body, the razor clam had struck and carved up a perfect canvas. The Flatmate lost herself amongst her own freckles. What is this part of my arm called? she thought. She could not name it, did not know if she had ever known the name for it. If she had, she had forgotten it. And why am I stroking it? She tried to push out other thoughts from her mind.

The Flatmate cornered her head to look back at Lil on the pavement again before stepping up and onto the bus. What a mess. Lil was a mess. Sliced and strewn into numerous chunks of meat, Lil was spread all over the pavement. Not a ten. Not anymore.

The Flatmate examined her hair in the reflection of herself in the bus window as she moved down the central aisle and came to a decision: if Lil’s pieces were still there in the morning, and if the weather had improved, she’d return and collect them up, try to piece them together to make sense of the events. The Flatmate would return and gather the segments of Lil up into a black sack and take the black sack back to the flat. In the morning. If the mess was still there.

The night is young, she thought to herself as she took the last seat on the bus, a tight squeeze, next to another seven, and Lil will, of course, look good in a bin bag.

“Is your friend okay?” the other seven asked. The two sevens, generic, both looked out of the window at the untidiness on the pavement. The shellfish continued to plummet like bullets from the sky. Some smashed open to reveal an ugliness on the inside which far surpassed the ugliness of their outer sides; others landed and remained tightly sealed.

“My friend? Oh, no. She’s not my friend, she’s just a flatmate,” she replied. She looked through the bus window glass and then she looked into the bus window glass, at the translucent version of herself, the carbon copy ghost, which was looking straight back, and she smiled. “I’m Leanne,” she said, and offered the other seven a wrapped mint from her bag.

“Thanks,” the other seven replied. “I’m Michelle.” The Flatmate, who from this point forth shall be referred to as LEANNE, laughed and made a joke and asked Michelle if she was shellfish and did she like shellfish and they wondered, together, if it had ever rained shellfish before, if it might ever rain shellfish again. The girls laughed at the same time and in the same way and the seafood storm outside stopped.

It became a pleasant journey. The two sevens discussed weather anomalies, ultraviolet lighting, and the benefits and disadvantages of living near the coast, and as one seven spoke, the other seven listened. It was a friendship of reciprocation. They travelled forwards, progressively, side-by-side, and by the time the bus reached its destination, both girls had become eights. They had a good night out on the town.

The next morning, Leanne, true and loyal to her thoughts, returned to the spot on the high street where the sky had opened up the night before to release its weaponry. She harvested all visible segments of Lil into a bag which she carried home, the weight of it increasing with each and every step, until it bore the mass of a thing upon Jupiter. She tucked the bag under her bed for safekeeping. Out of sight, out of mind, she thought, she was sure she thought. But she was still not sure of much.

The rent still needed to be met each month, there was no hiding that eventuality, so Leanne invited the other seven, Michelle, to move in and so, Michelle moved in, and from this point forward, Michelle shall be referred to as ‘THE FLATMATE’.

The girls were so similar. They shared the same sized clothing and shoes, the same preference for quiet over music, the same allergy to biological washing detergent, and even the same preference to do their laundry on a Thursday. Their coincidences were unalarmingly alarming, and where Leanne and the Flatmate did have any differences, Leanne found, in time, the Flatmate would come round to her way of doing things. She could be coaxed along, like when your reflection in a mirror develops a split-second delay, when your reflected movements lag slightly behind the adjustment to your overarching, real-time frame which you are certain you have just moved. You know the feeling.

The Flatmate was easygoing, easily moulded, fitted in and around Leanne and the flat by the sea like a second skin. Their similarities, they both agreed, were uncanny.

When they went shopping together, the Flatmate would come home with bags full of dresses, shoes, and jewellery almost identical to Leanne’s. Several nights each week, Leanne would find the Flatmate in her room, looking through her wardrobe, asking to borrow things, sometimes taking without asking. Leanne did not mind. It’s rare to find someone with such impeccable taste, someone who enjoys the same things in life as I do, she thought. Someone who admires the same art.

A few weeks into their shared tenancy, Leanne returned from work to find the Flatmate’s bedroom had become the mirror image of her own, as if a reflection in a mirror, with no split-second delay: the same Great Wave of Kanagawa poster blu-tacked above the headboard, an identical floral duvet neatly spread over the bed, the matching stack of books on the corner table. Leanne was not sure who had bought the books first. She still was not sure of much. Perhaps it had been her that had seen the Flatmate’s impressive collection and had noted the names of the authors down, visited a shop to purchase them. No, she was certain she wouldn’t have done this. She would have been thrifty, borrowed them from the Flatmate, returning them once complete. She liked to read, but she was no fool with money. What would be the purpose of such duplication?

Over time, Leanne started to feel as if the Flatmate might, deliberately, or perhaps without realising, be imitating her persona, but where it should have felt like a compliment, the mimicry began to leave her feeling stale. It was hard being the sole source of creativity within the small apartment, was tough bringing new ideas to the dinner table, starting fresh conversation all the time. The Flatmate would nod and agree and smile and follow her around all lost puppy. Like a ghost. Yes, this is how I have begun to feel, she thought, like I am living with a ghost, living at one as one with a ghost; alive but dead. And Leanne grew tired of this.

Despite her Flatmate—whose name she would often forget even though she was sure it should have been on the tip of her tongue—being most agreeable, most amiable, Leanne felt like she was either living alone or existing in parallel with a ghost. Or with a shadow of a ghost, the ghost of a ghost.

As time passed, in the small space of the flat, the girls spent the hours which sandwiched their working day largely in silence. They interposed only with brief exchanges, pleasantries. It was as if they were so similar, one knew what the other was to say before it became said. And sometimes, when they did speak to one other, short sentences rang out in unison, matched.

Snap.

Leanne found she’d become reliant on asking her own self for advice on what to have for dinner, about what shoes to wear with what dress, and so on, rather than discussing such things with the Flatmate. The thoughts within her head provided a more stimulating conversation, opened up a wider spectrum of unique, unpredictable suggestions than any discussion she could press from the Flatmate.

“Could I borrow a dress for tonight, Leanne? Maybe one of the ones you wore last week?” the Flatmate asked one Saturday afternoon, although Leanne knew the request was coming. The Flatmate’s voice came from the bathroom, the shower. The mist of the shower seeped out under the bathroom door, carrying the words towards Leanne, who had been perched on the sofa for some time, already ready to go out, already nursing an empty wine glass.

She thought back to the week before, a paper doll identi-kit row of nights out which had felt like every other night out: a blur of unoriginal conversation broken up only by the sour shock of sharp white wine. She couldn’t recall what they’d spoken about or what she’d worn. The last few months had left little of an impression on her hippocampus. “Which dress?” she whispered back, wearily, more to herself than to anyone else. Perhaps only to herself. She felt a little empty, unvariegated from anything else.

“Any of the ones you wore last week,” the Flatmate replied. “You looked amazing in all of them. Like a model.”

Leanne, snail pace, curled forwards in her seat and pressed the balls of her palms into her temples and tried to remember but drew a blank. “I’ll go take a look,” Leanne said and drifted back into her bedroom. But once she had crossed the threshold to her room, a room now identical to the other bedroom in the flat by the sea, she struggled to remember why she was there.

“I don’t mind which one, the green or the taupe,” the voice said; must have been the voice of her Flatmate, although it sounded as if it had come from somewhere deep within. Or as if the ocean had spoken.

Which one of what? A dress, Leanne thought. I am looking for a dress.

Leanne searched her bedroom, leafed through countless dresses hung neatly in her closet, but couldn’t recall which she had worn yesterday, let alone last week. Had something slipped down the side of her dressing table or got lost in a dark corner? Things often slide down the sides of spaces and become hidden, she thought. Don’t they? She knelt down and lifted up the valance sheet of her single bed, patted around with her hands, and pulled out the only thing which was under the bed: a full black bag.

Leanne had forgotten it was there, the bag. She associated the sight of it with the scent of a particular smell, but the specifics of the smell, or the label it used to carry, she couldn’t recall. It no longer smelt. She handled the sack, tugged it free, and the act of dislodging it seemed to stir up further memories, memories which had perhaps slid down, into a dark space. She looked at the bag and the bag didn’t look back at her. It was just a bag, after all. But the bag made her feel something. The bag made her feel ugly. Ugly both inside and out. But the feeling of feeling something, anything again, after all this time, also made her feel awake.

A floorboard outside of her bedroom creaked. Must be my flatmate out of the shower, wanting a dress, Leanne thought. Something to wear.

Leanne stepped back from the sack and turned away from it. “I can’t find what you mean.” She said this to the noise outside of her room. I can’t find meaning, she thought.

She came out of her room and searched the flat but found no one. Am I living with a ghost? she thought and remembered elements of the day when the sky became undone by a long, grey zipper, the day when she made it to the bus stop just in time before the heavens opened. The bag had been heavy to lug back to the flat. It felt lighter now, as she reached for it, and lifted it up to feel its weight once again. It felt as if it was made from less now. Could it mean less now, too, or more?

Leanne slid her shoes on and glided out of the flat with the bag. She travelled down the road and over the bridge and past a row of identical, bleak houses. Leanne continued to move until she reached the beach. The weak winter sun kissed the watery horizon as if it were floating directly on top of the flat ocean. The sun seemed to be held up and made more beautiful by the elegance of the sea underneath it. The beauty of the sun, she thought, is compounded by everything around it. And everything around it is made more beautiful by the sun. Everything is better in perspective.

She took her shoes off and sank her feet into wet sand and walked out until the water lapped up to the part of her leg between the ankle and the knee which she could not recall the name of. It was, after all, just another part of a body.

All this time, all these months, she’d lived here, by the sea, and had observed it daily, listened to it thanking her for staying close, but she had never stepped into the brackish water. It should feel cold, she thought. And it should feel better to feel something rather than nothing. But still, she felt nothing. Nothing physical, of hot or cold. Perhaps her soul felt a little cooler, or maybe it felt a little less haunted. Perhaps the something which had slid down the sides of her chest cavity, wedged itself deep within a dark place between her heart and her lungs and hoped to remain hidden there, had eased a baby toe free.

When she had waded out as far as she could without getting her clothing wet, she stopped and tried to make out her reflection on the surface of the water. Nothing distinct caught her eye, nothing beautiful or ugly, only ripples the colour of grey and blue and flesh and dress, which all moved in sync with her. But the coldness of the water had started to burn against her skin and the sea encouraged her on.

The girl tipped the contents of the bag out into the ocean, and the blurred reflection, with no time delay at all, copied. Dried pieces of something from her past grew larger and more beautiful as they became wet again and then dispersed and then became smaller and smaller and proportionately less important and less beautiful as they sunk.

She looked up to the sky which had become grey and considered if it might soon rain. Embracing the iced chill of the ocean against her skin and the voice of the waves, she walked forward and down. She walked until her mouth became filled with the coldness, until her voice became taken by the sea. With slow motion, she chased after the dissipating beauty with which she could never compete, but which, at least, stirred a feeling of something deep within.