The Scorpions of Azendara

by

Linda McMullen

previous next

Illumination

Contributors'

Bios

The Scorpions of Azendara

by

Linda McMullen

previous

Illumination

next

Contributors'

Bios

The Scorpions of Azendara

by

Linda McMullen

previous next

Illumination

Contributors'

Bios

previous

Illumination

next

Contributors'

Bios

The Scorpions of Azendara

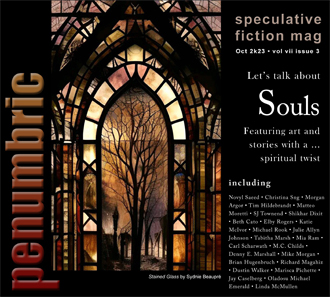

by Linda McMullen

The Scorpions of Azendara

by Linda McMullen

The chieftainess of all the scorpions felt the vibrations first, the distant, mantic rumble, from her cave traced by the very fingers of the jealous and righteous gods. She looped her tail over her children as they clung to her back. Then she summoned her clan.

“We must stand ready.”

Her guards stationed themselves in the slivers of shadow beneath overhanging rocks. The reports confirmed the worst of her suspicions, a horror the ancestors had consigned to allusions and whispers, an implacable menace that threatened their very existence ...

Man.

They come in great numbers, her sentinels reported. They come with their young. They come with fire ... The chieftainess sent out her most trusted spies to observe the interlopers, who added alarming details. They have come with burdens on their back. They bear weapons in their hands. They have occupied the great cave. Then:

They are digging.

They are building.

They are staying.

The chieftainess spoke to the clan, raising her pedipalp. “We shall not bow before these invaders!” Claws clicked in raucous approval. “We are an ancient body; we have fought drought and wind, predators and plagues. It is beneath our dignity to attack such mean prey as they. But we shall not cede our dominion. We shall live as we have always lived—and if these foolish men attempt to interfere with us, we shall teach them the meaning of pain!”

“All hail! All hail! All hail!” cried the clan, proud and—though they should never have confessed it—relieved to hear their aging chieftainess affirm the strength of the clan.

The chieftainess felt her young—surely her last brood—nestling against her back. She reclined into the soft sands to sleep, to close her many pairs of eyes ... but her central pair seemed to sight a human figure pacing beneath the starlight, as if its wizened back also bore the weight of many souls.

“Chieftainess!”

She awoke to two young scouts bounding into her chamber, forgetting her dignity, and their own. “They came!”

“Children,” she intoned. They stopped their exclamations and prostrated themselves.

“Better. Now, what is it?” demanded the chieftainess, rising, yet careful of the sleeping ones on her back.

“They have brought a gift!”

It was well that her young still dozed, or she might have been tempted to a less-than-stately pace. As it was, she discovered, at the mouth of the cave, a hand-smoothed rock bowl full of insects and spiders. A princely offering.

The scouts hastened to bring her a sample, but she flung her pedipalp into the air. “Wait! We must test it first.” An old story of a less-cautious ancestress had come to mind—the dénouement featured stilled claws and glazed eyes.

One of the scouts volunteered. He devoured a spider with visible relish.

Then they waited.

And waited.

As the sun rose in the sky, the scout’s appearance did not alter.

The chieftainess ordered a tenth of the mass delivered unto the gods. This done, she said, “Breakfast, everyone.” To her mate, she murmured, “The Old Ones never spoke of men with manners.”

“Perhaps they have learned,” said her mate.

The chieftainess said nothing. Her venerable ancestresses had taught her well the frailty of humankind, and how too often, tiny temptations too often wrought catastrophes ...

Still. A return gift was in order.

The chieftainess sent her scouts to observe the newcomers as they struggled to establish themselves, as they tucked seeds of hope into the sandy soil. The scouts reported dusty faces and gasping mouths. The seeds that struggled and smothered. The young crying for relief that would not come.

The chieftainess nodded. She summoned her strongest warriors, female and male, and told them what to do.

They assembled before dawn, awaiting the first groans of the just-waking humans. One female stole outside before the rest and saw the scorpions. And stopped.

Only the gods and the scorpions knew the shape of the underground rivers. The scorpions had formed themselves into an arrow, pointing at a spot where the waters flowed nearest the surface. The woman tiptoed nearer, as if fearing that the scorpions would strike. The scorpions tensed, knowing that that a human hand could hurl rocks that could crush their ebon exoskeletons ...

The woman knelt before the point of the arrow, scooping the sand out with her hands—until they came away wet. And the woman wept, but joyfully. Then she drew a swiveling path—not too steep—into the cone, so that the waiting scorpion could walk down, and drink first...

“Maybe they have learned,” said the chieftainess’s mate, when he heard the story.

The humans made their own well next to the little cone, which remained thereafter for the scorpions’ use. They drew forth water and made their gardens bloom. When the insects came to steal the fruits, the scorpions came to feast. And so they lived side by side, their numbers growing, and the chieftainess gave thanks within her inmost cave ...

The scouts reported the day the human leader died. They put his body in a hole in the earth and covered it, the scouts reported. They keened and crooned. They traced the shape of the death’s head onto their faces with ashes.

And, the scouts said, the new leader had come forth. He ordered his people to begin digging more wells. To plant more gardens. To deepen the well that the scorpions had shown them, which he claimed for his own ...

“Can we stop them?” asked the chieftainess’s mate.

One. They could stop one digger—could sacrifice one agent to assault a bare ankle—but at what cost? Their wary coexistence would end; every scorpion would become a threat and an enemy. The chieftainess sighed; her children thrummed against her back. Soon they would leave her.

“We can offer them a sign.”

The next morning, the scorpions had again assembled at the site of the original well—but this time, they encircled it, stingers foremost. The diggers fled at the sight of them, and the militants congratulated themselves—until the new leader came forth.

He was a stocky man of medium height, with a shock of black hair. He laughed at the scorpions’ array. And sat down to wait. He had his men bring forth a tent to shade him; his women brought him water and meals. The woman who had dug the original well seemed to plead with him; he cast her aside. The scorpions stood beneath the unwavering yellow eye and worried that it would cook them alive...

At last, their leader, the chieftainess’s sister, feeling her own strength ebbing in her limbs, cried out, “Stand down, stand down—seek shade!” Parched and infinitely weary, they withdrew to an outcropping, while the human leader smirked.

Three of their number succumbed.

The chieftainess gave them burials of honor, and admitted her griefs only within the confines of her cave.

The scorpions kept to themselves after that, and hunted no more amidst the human gardens, which attracted insects in droves ...

But the human clan grew, and the leader ordered an enormous palace built around the well. When it ran dry, he ordered his people to dig still deeper...

– and touched the sacred heart of the desert.

And that night, the sky blazed. The chieftainess recognized the fury of the gods, and the wrath the human leader had awoken against himself—and his people. He cowered within his newly built caverns, pretending that the fury of the heavens was only a storm...

The rains came—not the gentle fall that nourishes, but a torrent that washes all away. It slashed the plants in the humans’ gardens and tormented their animals. It eroded the foundations of the hopeful future homes ...

... and swept away the brave sentinels standing watch that night.

And after the rains came the sickness.

The new scouts—promoted in haste—reported more holes in the ground, more dirges, more ashes on faces. Animals swaying, never to rise again. Babes stilling in their mothers’ arms.

And the scorpions, too, struggled to find water uncontaminated with filth ... food untainted ... rest from the unceasing heat and the howling winds ...

The chieftainess considered all of this and said, “The human leader has brought the gods’ wrath upon us.”

It seemed she was right; the sun and the struggle proved unrelenting, and hunger stalked the land for all ...

“I will go,” said the chieftainess’s mate.

“What?”

“I advised you badly,” he said. “I thought they could be trusted. I will ... put this to rights.”

The chieftainess clutched his claws in her own, attempting to sway him: “You take too much upon yourself!”

“I have had a good life,” he said. “We have seen many of our young come into this world. But now, we are watching too many of their young leave it—too soon. It is time.”

The chieftainess lowered her head, and said, “May the gods bless you.”

He slipped into the palace undetected and stung the human leader while he slept. And then, exhausted, he allowed the servant to sweep him into the flames’ warm embrace ...

The next morning found the young woman who had dug the well outside the scorpions’ lair. She sat with her legs tucked beneath her, her palms flat against the ground, and her head bowed, which the chieftainess—who had agreed to receive the visitor—recognized as a pose of humility.

“I do not know if you understand my tongue ” began the woman. Her face began to express doubt that addressing herself to scorpions represented a sane course, so the chieftainess strode forward three steps and bowed her head, to indicate that she did. “We have injured you,” the woman continued. “And you us. Our leader died in the night. We found the mark of the sting upon him.”

The chieftainess waited. The woman wore ashes for the leader she had lost—but she had applied them in haste and with careless fingers, the chieftainess observed wryly.

“But ... we must stand together now. We are suffering and I—I imagine you must be suffering too. The gods have turned against us.” The woman swallowed. “I am asking for you to stand beside us.”

The chieftainess considered dismissing her. Her clan could survive without food, with minimal water, with diminished air.

And it was death to go against the gods.

The chieftainess tilted her head to the side, as if in question.

The woman smiled. “I ask you because we need help, and because I believe our future ways lie along the same path. And also because of the one bit of wisdom handed down amongst our people: scorpions cannot be frightened away—by anyone.”

Flattery would never move her—though she recognized the effort. But the woman’s look of determination in the face of despair—her understated courage—her determination to save those she loved ...

The chieftainess extended her pedipalp.

The woman touched her finger to it, and nodded.

Before dawn, the scorpions and the humans had reached the half-demolished palace surrounding the well, and had taken up their positions. The chieftainess rested on the woman’s shoulder. The woman took a deep breath, and glanced skyward.

Then she pricked the tip of her finger with a pin and let a drop of her blood fall into the depths of the well.

It was enough.

The gods appeared before them and advanced on the ruin in furious splendor. The legs of all the defenders trembled with the enormity of what they had done ...

The gods hurled balls of fire at the crumbling walls, summoned a blistering sandstorm, and rained stones upon their blasphemous opponents’ heads. The humans returned the assault as best they could with their primitive weapons, shielding their eyes, slinging stones at their attackers. Men fell, women fell, scorpions sank into the sand. The remaining scorpions dodged the infernal rain as best they could, and moved against the gods’ line—but the chieftainess saw her vanguard caught beneath a blaze ...

She wept ...

She could not have foreseen the result.

But she spotted it first.

The gods, it seemed, were not as impervious to mortal attack as they pretended to be.

The smoke rose from the corpses of the incinerated scorpions—the wind swirled—the gods shrieked imprecations as they inhaled the airborne venom, their senses inflamed, their legs giving way as their agonies overtook them. The chieftainess pinched her fellow general’s shoulder gently, to gain her attention; this achieved, she curled her pedipalp before her own face.

“Right. Thank you,” said the woman, who took the kerchief from her hair and wrapped it over her nose and mouth, then called to her soldiers to do the same. Then she urged them forward, into the breach ... blades clashed and sang, men and women fell and gods sank to their knees, until the woman herself had reached the battle line, and was swinging her knife at the throat of a god—

“Halt!” cried a god, in a voice that shook the firmament and set the very earth a-tremble. The woman lowered her weapon, and the humans followed suit; the chieftainess gestured to her soldiers to obey. They surveyed many reeling gods, screaming in pain, fending off venomous visions only they could see ... They themselves were sand-blasted, exhausted, and riven with thirst—but standing.

The chieftainess and the woman met his eyes.

“Explain yourselves. The scorpion first.”

The chieftainess spoke first, in a language only the immortals could understand.

Then the god spoke to the woman. “Now, human, let’s see if your story matches.”

The woman spoke, confirming the particulars.

“So the original offender is dead, then.”

The chieftainess and the woman nodded.

“We could simply destroy you,” the god said, gravely. “But we prefer to simply teach you a lesson.” He surveyed the scorpion and human bodies on the ground, the blasted landscape. “You have fought courageously and creatively, and we are impressed that two such different species could band together.” The woman admitted a smile. “We will thus withdraw the plagues and the winds and allow all of you to continue to inhabit this land, on the condition that you continue to show respect for the other.”

The chieftainess and the woman looked their gratitude.

“Nevertheless, you have also defied us.”

The woman’s smile faded.

“Woman,” he said, “you evoked this conflict by allowing your blood to mingle with the holy waters. It is fitting, therefore, that your blood shall flow no more, and you shall never bear children. But,” he continued, “you have also proven yourself a more capable leader than your predecessor, and you shall rule your people. Then you will pass the mantle back to the former leader’s youngest son, who did not fight here today.”

The woman bowed her head.

“Chieftainess,” continued the god, “you chose to bind yourself to an unholy cause, knowing better than your conspirator the folly of your choices.” The chieftainess acknowledged this. “Therefore, you too shall be the last of your line. You shall raise up the daughter of your first-slain scout in your place.”

The chieftainess blinked her many pairs of eyes slowly. A blow. A horrific blow—and yet she must be grateful ...

“And one thing more,” said the god, gazing over the arid landscape, taking in everything from the mountains to the caves to the insects buzzing over the just-ripening tomatoes in the humans’ garden. “You may all remain ... but in a state of constant precarity. The winds will haunt you and the rains will only come when you have courted disaster. A reminder—that you are here on sufferance.”

The chieftainess and the woman bowed deeply. The gods vanished. And the two of them exchanged a look of understanding as the woman set the chieftainess down, and each moved to prepare her followers for an uncertain future.