The Freelancer

by

Laurence Klavan

previous next

Peter O'Toole

Lunch 2032

(recharge)

The Freelancer

by

Laurence Klavan

previous

Peter O'Toole

next

Lunch 2032

(recharge)

The Freelancer

by

Laurence Klavan

previous next

Peter O'Toole

Lunch 2032

(recharge)

previous

Peter O'Toole

next

Lunch 2032

(recharge)

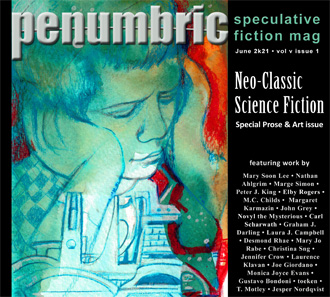

The Freelancer by Laurence Klavan

The Freelancer

by Laurence Klavan

Ranger noticed the other boy there, but he didn't think much of it. There were occasionally kids around the office, what was the big deal? Still, he didn't go out of his way to be the boy's pal or anything. Fuck that—why? He ignored him.

"I'm Trey," the kid said, having no choice but to volunteer the information and so seeming weak, like he couldn't take the silence. Ranger nodded, not saying his own name, being withholding, that's what they called it. He shook the hand offered quickly—not weakly, not like limply, firmly but fast, forcing the other boy to come up with the question.

"And your name is ... ?" Trey omitted the "what is" part, the "what is your name?" part, because it was too exposing, like a dog showing its belly. The kid made it a statement, an inquiry that needed an ending, because an actual question would have been enfeebling—a question mark was cowardly, Ranger thought, not really knowing why. Anyway, it was a smart move by Trey; because of it, he respected the new kid and responded.

"Ranger." He only had the one name, which pegged him as an orphan and dared the other boy—any boy, actually, but this one at this moment—to comment on it, which Trey didn't do. He just nodded and started out of the office, as if on an assignment, which bugged Ranger, for where did that leave him? Anyway, it could have been worse—another boy had once barked when he heard "Ranger," because it sounded like a dog's name, which bought the kid a beat-down, even though he thought it funny, he had to admit. In Ranger's world, everything was turf, how you walked, what you wore, even the words that came out of your mouth, and you had to protect that turf or concede it to someone else.

Now that Ranger thought about it, though, he realized Trey hadn't said his last name, either. So maybe he was an orphan, too, which made sense. Brenda preferred to hire them and send them out, felt they had less to lose—so was that what she'd done today, hired and sent out Trey instead of him? Why? What had he done wrong? Feeling angry, because it was less weak than feeling hurt, Ranger looked inside the office for the older woman who was his boss.

He found Brenda faced away, at her desk, talking on some new device Ranger couldn't afford and which only older, rich assholes had. Maybe when she wasn't looking, he'd take it; that would teach her for dicking him around and making him uneasy. He was her best boy. Not that he had to hear her say it, he wasn't weak like that, but—Brenda ought to know Ranger knew his own worth and wouldn't put up with any shit.

Still, it took her forever to turn and see him and even then she just raised her eyebrows once, as if telling a delivery boy to wait, she'd be off in a second, and swiveled back the other way. Ranger wasn't used to this kind of treatment—who she did call day and night and know would accept any assignment? Him! Until recently, anyway, and not because of anything he'd done; he'd been more active and aggressive than ever, scouring sites for remains and such. But Brenda had let him go two whole days without a call and then, well, what was that Trey piece of shit doing there, anyway? What gave?

Brenda hung up—or got off or blinked off or whatever the hell you did with that device; Ranger would find out when he stole it. She turned and took him in with just the merest of glances, the way girls sometimes avoided his stares on the street—not all girls, don't fool yourself, plenty smiled at him, because he was good-looking, getting to be, anyway, fifteen was the start of a long and happy love life, he had no doubts at all in that department, believe me.

"What's up?" she asked, and her voice was flat.

"What do you mean?"

Ranger couldn't help asking. He hated that sound in her voice, that "get it over with" sound at which Brenda was so good; he'd heard her use it on lots of people but never with him. Someone told him that Brenda had once been a big blogger, a gossip blogger, like she had posted stupid shit online about celebrities that people supposedly paid to read, subscribed to read, that was the way it had been said to him, paid every month to read, like money was something they couldn't wait to get rid of and so would use to buy any stupid old shit in order to have less of it, like money was poison in a snakebite you sucked in and spat out (he'd seen a TV show once about that over someone's shoulder on the train). Anyway, Brenda had done well at it until her site went under and she got fired and went to work for the Muth Co., where she sent out kids like him—not like him, him, until today!

"I mean," Brenda said, "what do you want?"

Now her tone had turned nasty instead of indifferent, which at least gave him something to work with. Ranger could fight, spent half his day doing it, in one way or another. So he preferred Brenda being pissed at him; it was the ignoring, the back-turning, the giving up on him that he couldn't take. He answered, with a similar air of anger, "To work—what else?"

Brenda looked confused. "Didn't I just give you something?"

Brenda had backslid into the dismissive territory that made him so unsettled. It was like she thought Trey had been him or hadn't cared what boy had gone out. Look, maybe she'd barely even met the other kid; maybe Trey had come around looking and gotten nothing from her, and that's why he had left. Ranger didn't want to deal with it any more, it was driving him crazy. So he kept the edge in his voice, for at least it felt normal.

"No. What, you got a worm in your head?"

It wasn't witty, but it got his point across—he'd insulted Brenda, which meant he wasn't afraid of her, he was tough, which she'd always admired, for she was tough, too, and mean, and that's why they'd gotten along. (Ranger sensed that, as an adult, Brenda could always be meaner than him; he was fifteen and fifteen was, at this moment in this world, still not grown. Ranger may not have wanted to know the whole story yet, for—even though he longed for the sexual love that would mean he was a man—he'd have to leave a lot behind to grow up, and that made him afraid.)

"All right," Brenda sighed, and logged back onto her new device in a weird way, for she made no move but look down. Was she trying to get rid of him? Ranger felt so shaky he was interpreting everything negatively, and he hated that. Anyway, she was about to throw him a job, and that was good.

"There was a nightclub opening last night," Brenda said, "and some sort-of stars were there." She scribbled on a piece of paper, an archaic custom she'd maintained, which gave her a timeless quality, as if she'd been sent there from the past or was maybe just aging slower than everyone else. Ranger thought she dressed like a younger woman, too, with her white buttoned-down shirt stuffed into her tight skirt and unbuttoned halfway down, exposing freckled breasts that Ranger didn't want to see but couldn't stop staring at, surprised he'd give a shit, since she was old enough to be his, what, great-grandmother, but knowing he had sex on the brain all day every day being fifteen, and also feeling bad because Brenda represented someone he wasn't supposed to desire, even though it was really all right, they weren't related—anyway, she tore it off, the piece of paper, and pushed it across her pristine black desk to him.

"That's the address."

After reading it: "Where is that?"

Brenda looked at him—what was the word?—witheringly, as if to say, do I have to do everything? This was not okay but at least not unprecedented. "Use your thing, for Chrissake."

She meant Ranger's pocket GPS gadget, the Beamer or whatever it was called, that got him to and from the blast sites—he'd forgotten for a second that he'd been issued one. Brenda had reminded him as if telling him to wipe his nose or do his homework, like—oh, why not come out and say it, stop being cute, he thought—the mother he didn't have and never had had.

"Okay." Ranger said, apologetically, which was a departure, given his typical toughness. Maybe he'd intentionally forgotten about the Beamer, in order to be reminded by Brenda in that motherly way. In any case, he felt better, being berated by her. And that was enough for today, he thought: he'd gotten all he needed from her, a job. He turned away—but Brenda had already done the same thing first, which was weird.

Using the Beamer, Ranger took the train to the bus to the bus-train and back to the train-bus (or the Trus and the Brain, as other orphans called it). They let him out in the ass-end of town, at the site of the club Brenda had mentioned. It was now a skeletal and rickety frame helpless to protect a smoldering pile of wood, steel and rocks. The explosion had taken place last night, and the minor celebrities in attendance had been from the music business, low level wankers who sang and danced. It was Ranger's job to get past the police and confiscate any items that might retain the DNA of these D-listers blown to bits, taking from the skin, intestines and other organs now scattered upon, dripping from or wetly decorating the wreckage.

And this was his particular gift, his specialty, weaving in and out even when the cops told him to get lost, which they usually did. Ranger was almost like a rat (he didn't mind the comparison—rats were cool) that could shrink to slide under doors. Some cops compared him to smoke, wafting here and there before disappearing altogether. They said it with reluctant admiration, even though he fucked with their crime scenes. Was it that they didn't blame him entirely, because he was only a kid and a kid without any family or permanent home (he was currently sleeping on a cot in a disfigured building that once had been a church—whatever that was). Or was it that there was a kind of weird connection between cops and crooks, because one in a way defined the other by being its opposite, the way you were defined by those you loved and hated? It was the closest Ranger had come to being known by anyone, except for Brenda, who hired him and sent him out.

"Hey!"

Today the cop had to yell—not because he was infuriated or even annoyed but to show his superiors that he was doing his job. In any case, Ranger whipped by him, went under the crime scene tapes, both actual and laser, to scoop up whatever pieces of furniture or floor might hold the most and least melted remains.

He had a plastic bag over his shoulder, like—what was the name of that bitch somebody mentioned used to exist?—Johnny Appleseed, but Ranger plucked and picked up, didn't put down and plant. He'd even worn his grooviest gloves, which were black leather but super-thin and close to the bone, like a second skin. Today his job was made easier by the sun, which shined on and made sparkle what the elderly called bling, vestiges of chains, bracelets and earrings that drooped on door frames and toilet stalls, like in—again, who was the dude?—a Dali drawing, retaining aspects of beings. The sun was like his spy, working for him, because he was as big a badass as the Earth! In his element, Ranger was now snapping off and stuffing down so fast, it was like he wasn't even stopping, like he was simply swallowing stuff, and you didn't stop to do that, did you? You did not.

Then Ranger did stop, screeched to a halt, that was the expression (he'd been taught to read by an old bum, but he had to break it off because of what the guy really wanted from him, and Ranger had been just a little boy, Jesus fucking Christ, whoever he was). He planted himself intentionally in anger the way someone else might mistakenly in mud.

Trey was there.

The little asshole from the office had gotten there ahead of him—this was where he'd been going when he left, he had been assigned by Brenda! Hadn't he? How else was he doing this now, yanking and placing bits of broken glass and black charred wood in his bag? It was a better bag, too: was that a new, more opaque plastic? Why didn't Ranger have that?

Ranger felt as if something was painfully hanging from and falling off his chest, like bricks breaking off a building on fire and landing on the ground. Suddenly, he wasn't so concerned about what he'd collected: it all seemed puny, second-rate, and superfluous (though he didn't know that word, only knew it was unnecessary). Even the money he would make was minor compared to the betrayal he was enduring; one thing could not compensate for the other; it was like being offered a blow job for a bullet wound, you know? (He had to couch it in vulgar terms because his need for tenderness was so great and too embarrassing, offered him up to the vultures, coyotes, and crows in the steel forest where he lived.)

So Ranger upended and emptied the bag, scattering the last evidence of those stupid failed singers and dancers—those human beings—making it unlikely they would ever be reborn. (He knew what the stuff was used for, what Brenda had been hired by the Muth Co. to hire him to do: retrieve and sell the DNA of near-nobodies, that was the best they could get these days, once their celebrity business collapsed; he wasn't stupid, just uneducated). Then he fled the scene, the crater that had been a club until just a few hours ago, until some psycho with a religious or political reason had turned it and everyone in it and himself into just vestiges of themselves, suitable for scavenging by the likes of Ranger.

He retraced his steps and passed the first cop again—who didn't care, maybe had never cared—going like in reverse, except nothing was rewound and came to life again. In fact, everything seemed deader than when he'd arrived; Ranger, too, felt less alive. (That wasn't true: because of Trey, tears were now jumping from his eyes as if escaping his burning building. His face was as hot as his heart, and that felt vital in a new and awful way.)

Wiping his cheeks, Ranger staggered from the site with no destination in mind, checking over his shoulder to see if Trey was still there. The bastard was, yanking shards from the shattered site and pressing them deep into his better bag, looking like a slave, picking cotton for his masters (Ranger had seen a music video about that once). Yeah, well, what did that make him? Ranger was simply competing to be the best scavenger, the finest stealer of cells, nothing for which a person should be proud, orphan or not.

But you know who was the worst? Brenda, because she was older and should have known better; she had sold celebrities before and was now selling losers when they were nothing but smears and slime and ripped ribbons of themselves. It was over, Ranger thought, he was through working for Brenda, picking up his pace as if actually on his way somewhere. Then, of course, he slowed and stopped because he was lost.

Ranger patted his back pocket, expecting to feel the familiar bulge of his Beamer, but he only touched his ass. The device had fallen out—or been swiped by the cop as Ranger sped past him, stranger things had happened. Instead of increasing them, desperation dried his tears now; and he looked every which way, with the world fiercely in focus. He saw closed stores and abandoned construction sites, no people—except, wait, there was a girl his own age standing on a far corner, tentatively raising her hand, either to swat something away or wave, he wasn't sure.

Ranger decided she was waving. He waved back, his fingers curled, seeming to scratch his nails on the chalkboard of a school he'd never attended. She smiled, which was his signal to cross; he was fifteen and still learning how it worked. She'd done her job, now he had one to do. It was a relief, and he did not delay, for she looked like the future and was not far away.

When he reached the other side, Ranger saw how small she was—everything about her was short, including her hair, which was in a buzzcut. In fact, she looked a little like him, only her face was softer; his was growing harder and darker every day, as if being cooked by the flame which was the time since he turned twelve. She had on a T-shirt and khaki shorts, so was a like a ranger, too.

"Are you lost?" she asked.

"Yes."

He had just blurted out the answer, because who had ever asked him such a thing, ever asked him anything about how he felt? It was like that "maneuver" where they hold you hard and the chunk of food choking you popped out; she'd held him that way for a second.

"I lost my ..." Suddenly, he couldn't remember the name of the stupid device; he tried to form its nebulous shape with his fingers, then gave up.

"Where are you trying to go?"

"I wasn't," he said, again ultra-honestly. "I was working."

"Where?"

He nodded at the ruins, which from across the street looked like a castle leveled centuries ago, an impossible place to do anything.

The girl was baffled. Then she shook her head, slowly and meaningfully, his occupation becoming clear. "Oh. Right."

"But I just quit," he said, half because of how she'd said it and half to see how it would sound. It sounded good, but a little unnerving, like the click when you close a door behind you without the key.

"What will you do now?" she asked, seeming to approve of his decision (or maybe he was just imposing this and she meant nothing by it and was simply making conversation; it wasn't clear; he hadn't talked much to girls).

Ranger shrugged. Coming from behind a cloud, the sun made him squint and seem even more uncertain. The sun was again giving him a hand as it had when it exposed the remains; now it said, show her how unsettled you are, go on, don't be embarrassed, she's here to help you—or so he imagined the sun said, still anthropomorphizing nature like a child.

"Where do you live?" She was grilling him—and literally, too, for the sun was extra-hot, assisting him.

Ranger had been honest with her the whole time and would not stop now. His voice sounded steeped, moist. "Nowhere."

The girl nodded and asked one more thing—"Hungry?" Before he could reply, assuming his answer, she turned to go. She was way ahead of him—not actually, they went side by side.

"I'm Shane," she said.

"Ranger," he said, and both their names were like places or positions or inanimate objects, something else they had in common.

Then he saw where she lived.

It was a real house—with a front door and working windows on its several floors. It had even been painted sometime in the last century or some other time Ranger couldn't understand. It was completely isolated on its block, where only suggestions of once towering, now obliterated structures were scattered on its either end.

"Come on," Shane said and took his hand, a touch which while innocent (and he had removed his gloves), at fifteen sent a shiver through him.

The two went through the front door, and it was immediately cool inside, though he heard no hum of air conditioner or fan. The house was sparsely furnished, with worn pieces that appeared to have been picked off the street, some even charred or hobbled from their own explosions. Ranger smelled a weird and dizzying mix of baked bread and—was it steak or chicken? He had had so little meat in his life that he couldn't tell.

"You're just in time for dinner."

It was a woman's voice. Emerging from around a corner was in fact a woman, probably as old as Brenda but looking older because she was unadorned. Her hair had gone gray (Brenda kept hers the color of fire) and she was soft and billowing where Brenda was hemmed-in and taut. Maybe it was her sort of sack dress, which moved here and there, relaxed and playfully indifferent, as she came forward, unlike the military stiffness of Brenda's shirt and skirt. In her oven-mitted hands was the bread Ranger had thought was there, smoking benignly and in a basket.

"I brought a guest," Shane said.

The woman stopped and looked at Ranger. For a second, her face registered confusion; this was quickly replaced by an expression he took to be welcoming but had seen rarely and not recently at all.

"Okay," she said. "I'm Marilyn. Shane's mother."

Ranger didn't answer, surprised. He thought Shane's not saying her own last name meant that she was orphaned. Now he knew it was her just being easy, friendly, and informal.

These qualities were present in the way they ate, too: sitting at a big table in a dining room with open windows on every side. Somewhere else, Ranger might have felt on display, imprisoned, and judged. Here he sensed they were hiding nothing, were celebrating themselves, and offering up places for still others to take.

"This is delicious," he said, chewing—steak, it turned out—deliberately, to appreciate each bite. The conversation was casual and considerate—no one asked him prying questions; it was as if he were a soldier and they didn't wish to remind him of the carnage he had witnessed or caused. Still, they didn't avoid the issue altogether.

"It's so sad about the club," Marilyn said.

"It seemed hopeful that they'd built it on that block," Shane added.

"Like the neighborhood was coming back."

"Right. But no."

"It turned out to be just another target."

Shane and Marilyn had a rapport that fascinated Ranger. They didn't quite finish each other's sentences, but their words were connected, as if holding hands; he was embarrassed to imagine such a corny thing, but they'd inspired it. What most impressed Ranger about the meal (besides the food, of course—and that included the home-made dessert of some kind of fruit pie; he wasn't familiar enough with fruit to know which one it was) was Marilyn's focus on him. When she wasn't overtly observing him, she was sneaking peeks at him from across the table. Ranger had always been studied with suspicion by others to, say, see he didn't steal (which he sometimes did, of course). But this woman watched him with worry; her glance was the equivalent of someone kissing his forehead for a fever, something no one had ever done. He could not help leaning in to catch more of her concern, as if it were the spray of the sprinkler that had cooled down orphan kids when he was little (sometimes increasing until it was strong enough to wash them all away; it had been a trick to flick them off a street). Marilyn meant for him to be bathed in it, he could tell; this time he wasn't making it up or misinterpreting, as he did so often other people's intentions, unused as he was to and craving as he did human kindness. When she cleared the dishes and left the room, declining his help, acting as if he had exerted himself enough today, it was as if the room grew dark and dull without her.

"You're staying over, right?" Shane asked, but it wasn't a question, a double-check.

Later, Ranger lay on a big bare mattress in an otherwise empty room on the ground floor. He curled up there like a baby too young to have a blanket, not strong enough to keep from suffocating beneath it. Shane brought him a thin sheet, decorated with lambs and a female shepherd he didn't know was named Bo Peep. She draped it over him solemnly, the way you would a human sacrifice, which made them both laugh.

"I don't usually use one," she said, "but you might get cold."

Lying face down, already almost asleep, he felt the mattress shake. And Ranger understood: this was where Shane slept, too.

The bed was big enough that he barely knew she was near him, and she didn't pull on or ask to share the sheet. Still, with the filmy fabric over his ears, he could hear her breathe. He glanced down at the foot of the mattress and saw her shoes, shorts and shirt piled on the floor, a pair of white underpants on top, like the scoop of vanilla ice cream that had been on the pie for dessert. He had removed his own clothes already.

Ranger curled into a smaller ball, bent on creating more distance between them. Yet he couldn't keep from getting hard, his penis like a rock between his thighs with which he couldn't help but hit someone. This shifted the sheet, exposing a shoulder, and Shane lifted and placed it back on him, as a sister might. It fluttered there like a tongue and, helplessly, he ejaculated, careful to catch the cum with his thighs so as not to stain the sheet before he passed out again. The next thing he knew he was on his back, his legs completely spread, the sheet kicked to his feet, hot wet sunlight pouring on him like concrete, and Shane was gone.

Ranger moved into the house. Whatever stuff he had in the church didn't matter—he kept most of what he needed on his person, and the Beamer had been lost. He did chores around the place; even the nearly empty areas needed cleaning. Sometimes he was given money by Marilyn for food and ventured out to the few stores open in the neighborhood; other times, he negotiated with people on the street who hoarded goods. There were neighborhoods like Brenda's that had good security and so had not been devastated, and he would secretly travel there to bring back better things. Whenever he returned, Marilyn gave him that worried look he loved.

At night, they would gather around Shane's small device and squint to watch films or TV shows. Neither woman asked him anything about his life; they still treated this time as his convalescence. In fact, Ranger was so exhausted he slept long hours, often with Shane beside him, on the bed bare but for the sheet. He did not consciously touch her, but sometimes he would wake up wet again and wonder what had happened. One morning, he found a pubic hair (not his own) in his mouth, and Shane again was gone. They didn't say anything about it but blushed when they were alone, doing the dishes or something.

Ranger noticed that he looked older now. He soon found shaving equipment and a deodorant left for him on the glass ledge beneath the bathroom mirror. He taught himself how to use the razor and cut his nose, lip, chin, and cheek, which made the woman both sympathize with and laugh a little at him.

Occasionally, in one of his shallower sleeps, he would hear what he believed were bomb blasts from blocks away, reduced to dull thuds in the distance. If he remembered in the morning, he would check news sources and read about another event or upscale venue successfully targeted. Ranger would bitterly wonder who Brenda had sent out to scour it—Trey? Was that that little weasel's name? Then he forced himself to forget.

Sometimes, he would open the door to strangers seeking Marilyn who had no interest in talking or even leaving a message with anyone else. One of these people smelled of sulphur and another was out of breath. There were calls, too, and texts for her that Ranger answered or by accident intercepted.

"I forgot to mention," he began to say, one night in bed. Then he told Shane about such a visitor. Lying beside him, Shane didn't answer for a second, and Ranger almost fell asleep before she did.

"Did they say anything?"

"Who? Oh. No."

"You take a message?"

"Sorry. Should I have?"

"No. It's fine. Forget it." And her last two words didn't seem a suggestion but something stricter. This was another time that Ranger woke up feeling he'd experienced an exciting event while asleep—his skin was tingling—and wasn't sure if it had been a dream.

* * *

Then Marilyn apparently decided she had left Ranger alone long enough. At their next dinner, she asked him questions. They felt to Ranger like she was opening his Army backpack, trying to get a sense of what was inside, the way a mother would want to know how far in deed and feeling her soldier son had gone from her.

"You used to work for someone?" she asked, passing delicious mashed potatoes to soften him up.

Ranger nodded, giving himself a scoop of the creamy, highly buttered stuff.

"Not for yourself?"

"No. How could I do that?" It was the first "attitude" he had shown since coming, a sign that he was either more at ease or suddenly threatened. Either way, it surprised him to hear.

"Who was it? Brenda?"

Ranger had just slapped potato on the piece of steak he was about to stick in his mouth, so it looked like a white toupee on top. Now it slid a little down the side as the question made him stop. "Yeah." He popped it into his mouth, making it impossible for him to say more. How'd she know about Brenda?

"Right," she said, as if it was obvious. "Did she fire you?"

"No. I quit." Are you kidding me? he wanted to say, but kept his head.

Marilyn nodded, as if having figured that much, he was glad to see. Her tone changed as she herself stopped eating and watched him. "You tell her why?"

"No."

"Just walked away?"

"Yes." He didn't mention Trey; that might make him seem small.

"Have you been in touch with her since you left?"

Ranger looked up, pressing a piece of bread into gravy as a child would his boot into a puddle. The inquiries were starting to annoy him. "Of course not. You've been here. You've seen me."

"Maybe you should let her know you're okay."

Ranger didn't reply. Marilyn's tone was the aural equivalent of her worried looks; there was a warmth to it that he was unfamiliar with. Yet he didn't delight in it as he did her glances, which he still sought out. The questions made him realize her attention could be rigorous, her love (and he knew that's what it was, he wasn't stupid) required things of him; it didn't allow him everything. He didn't like that. When you were neglected—dismissed, even loathed—you were left alone.

"Why don't you go see her?" she said.

Ranger wanted to tell her to stop, stop pressing me, let me eat in peace, just—look at me, that's all I want. Instead, surprising himself even more, he blurted out, "Because she's finished with me, that's why."

He was quiet after this and done with his dinner, pushing away his plate. He knew this contradicted what he'd said before, that he'd quit. But he didn't mean it literally: Brenda had let him go, not fired him, there was a difference. And now he spat out a sudden cry that was like rotten wet meat choking him, covered his face with his hands, sticky from the buttered bread, and wept.

Marilyn let him; she didn't interrupt. When he could cry no more, he realized his moans had silenced all other sounds. His ears cleared, the way they do when you descend from a great height. He heard Marilyn sigh, with compassion.

"I'm sure," she said, "that that's not true."

Marilyn made and packed him a lunch, which she amusedly said she wanted to wrap in a napkin and put on a stick at his shoulder; but he'd never read Tom Sawyer or any similar story, so he didn't reply. She wrote a note, told him, "This is for Brenda, not you," folded it twice and placed it in his back pocket, where the Beamer once had been. He would have to find his way there and back on his own.

"Can you do that?" she asked.

"Yes," he said, without thinking.

Ranger looked for Shane to say goodbye, but she wasn't around, and she'd already been asleep when he'd come to bed. He had a funny feeling she was avoiding him, he didn't know why. He remembered that he had been recently interpreting things negatively, so he stopped. Still, it felt as if Shane had done her job, the way a worm is finished when a fish hangs on its hook. Ranger hated the image, but he had it in his head, he couldn't help it.

He re-traced his steps to Brenda's. This time, there was more life the longer he went in reverse: buildings were reconstructed, people existed again. When Ranger entered her office, he expected to see a crowd of new kids there—conscripts, he now considered them; this was how Marilyn and Shane had made him feel. But the waiting area was empty and, though Brenda's door was open, he heard nothing from within. Ranger advanced and stepped onto its threshold as if approaching a precipice.

Brenda was behind her desk, staring right at him. Her new device—was it one even newer?—lay discarded on the reflecting surface of her black desk, as if having revealed something she'd rejected. Suddenly, he couldn't remember how long he'd been gone, a month? Six? Brenda appeared older, but maybe it was he who had aged. She looked at him as if he'd been a child when he left and was no longer.

"Look who's here," she said.

Ranger didn't know how to reply: her tone was as closed-off and hard-boiled as ever, and allowed him no way in. And her look, unlike Marilyn's, didn't land on him like a soothing hand but went through him without stopping and hit the wall at his back.

He waited, wondering if she might communicate with him as she always had, by sparring and giving him a job. But she only blinked, expecting him to say the next word or make the first move. The situation was both the same as when he'd left and worse, for he'd hoped it would be different.

He threw the note on Brenda's desk.

"What's that?" she said.

It was weird: each woman communicated in this archaic way, which was both personal and perishable, a form that highlighted one's handwriting with all its looping and stabbing idiosyncrasies that could be removed and never recovered, unlike a computer file or a person whose DNA he scooped up. It was as if both Brenda and Marilyn knew their relationship with him was temporal and would exist longer in his memory than in any other way.

"See for yourself," he said.

She looked at him as if he knew what it contained. Yet Ranger had obeyed Marilyn and not read it.

Brenda unfolded the paper and didn't blink for the short time it took her to take it in. Then she closed and placed her hand upon it, not letting Ranger have it, keeping it between the two of them, Marilyn and her.

Ranger had assumed the note was an explanation—even an apology—for why she'd kept Ranger so long, where he'd been, what he'd done. Yet it was too short to have said all that. And Brenda's expression had if anything hardened; if she understood anything better now, the knowledge hadn't made her more compassionate.

"Thanks," was all she said.

Ranger waited and kept waiting, but she wouldn't be the one to break the silence or crack a smile. He knew he was stronger than when he'd left and swore he would not be the one to weaken first. Yet Ranger also knew that Brenda was still better at this than he. Helplessly, he exhaled and in the breath came his capitulation, a question released like a dead rat flushed from a drain pipe.

"You got anything for me?"

There was silence again. Ranger's heart sped up. A smirk came onto Brenda's mouth, lifting the right side of her upper lip, plumping her cheek and closing one eye: everything connected, nothing accidental; dismissing him was an instinct. Then she stopped, as if it were petty—unprofessional—to take pleasure in his defeat.

"No," she said. "Sorry." And she reached for her device—to, what, call another kid?

Ranger left, his face burning, lacerated by losing to her once more when he'd been most determined to win. He rode the train-bus and bus-train, the Trus and Brain, back to Marilyn's, the journey more than memorized, now second nature. He was never going back to Brenda, that bitch, whom he hated now; he had not been able to even think the word before.

As he went, the landscape was again stripped of features; there was less and less to look at. He saw the bones of buildings, only parts of people, and felt this was his future, where he belonged. Goodbye to Brenda, that bitch, whom he hated. He had a real home now and was almost there.

When he got on the street again, rain fell, as hard as he had ever seen it, hurting when it hit his face, like a door opening on him again and again. Ranger hadn't brought an umbrella; that was for weaklings and anyway would have done nothing in a deluge. The water soaked then melted away his shirt; he peeled it off in pieces and made his way to Marilyn's in shorts, looking at last like someone's diapered child.

Yet he couldn't get inside. A pair of policemen stood guard, preventing anyone from approaching.

"What's going on?" he asked.

One cop looked at him with the usual contempt and didn't answer.

"I got to get in," Ranger said.

"Why? There's not a lot to steal." Snide: hurtful.

"Because I live there now, that's why."

Now the cop didn't find him funny. "Go away."

While Ranger was technically retired, it did not mean he had lost his skills. He quickly employed a move that was part limbo dance, part sliding into home, though he had never heard of either thing. Before the cop realized it, he was inside.

In the few minutes he was free, Ranger saw no evidence of anyone living there; and in the skewed position of his mattress, the broken cups in the kitchen, and—unless he was hallucinating—the small bloodstains on the wall, signs of a struggle that had ended badly. There was a faint aroma of baking bread, but he thought it might have been his imagination.

This time, the police were not jaded about his escape but made to apprehend him.

"Where are they?" Ranger asked, as they held his arms so he wouldn't hit them anymore.

Ranger slept in the hall, for the door was locked. He had escaped the police and didn't want to lose any time before finding the person he thought responsible.

Waking him, Brenda's door opened.

Had she slept there, as he had? Did she always stay in the office, have no other home? Was there even more they had in common? Brenda looked down at him as if at the delivery of something she had not ordered. Then, saying nothing, she turned and went back in.

Ranger stumbled after her, sick with fatigue. Never facing or addressing him, the older woman opened her blinds and let in the rude morning light. For a second, he understood and marveled at the fact that she worked there alone, except for freelancers, was the only permanent person. When everything was exposed, she moved toward her desk.

"What," Ranger said, "were you jealous?"

"Me? Of who?" She took no time to consider the question.

"Did you make up some story? Tell the cops a stupid lie about her?" Before she could answer, Ranger started screaming: How much he had always hated her, how he hated her so much now, he would kill her if he could. Because Brenda wouldn't have him but wouldn't let anyone else. He had no control over what he said. Ranger couldn't stop and soon was unable to express any words. He was in pieces, his heart on a spike like those remains at the club.

When Brenda hit him, it wasn't to stop him, to slap sense into him, like an actor in an old movie he hadn't seen. Brenda didn't seem motivated by helping him with tough love or whatever was the ancient expression. She seemed spurred on by anger alone, by the need to shut him up.

After she had finished yelling—calling him every name for "fool," whacking him back and forth with both hands, as Ranger covered his face and sank to his knees, not fighting back—she picked up the piece of paper given him by Marilyn. She dropped it on him as if it were a final, crushing stone. It fluttered from his face to his feet.

"Read it," she said, panting, "for God's sake."

At first, Ranger didn't move, shaken as much by his own reaction to Brenda as Brenda's to him. Sniffing back a drowning wave of salty water, his fingers trembling, he reached for the note, opened it, and did as he was told.

Ranger was just a good enough reader to get the gist. It was an offer from one woman to the other. Marilyn said that she knew when bombings occurred because they were done by her people. If she shared this information with Brenda, her freelancers could arrive on the scene before anyone else and give the Muth Co. first dibs on the remains. An arrangement could be worked out between them and relayed by Ranger, who could be their carrier pigeon. There was no mention of alerting the authorities and stopping the bombings before they took place.

Ranger dropped the paper on the floor, where it lay open. He imagined fumes flying from it, smoke the result of pestilence, the steam off shit. He looked up at Brenda and felt it was fitting that she loomed above him. She was better than Marilyn, whom she had punished. In the world in which he lived, Brenda was good. She had tried to protect him. It was the most and only love he would ever get.

"Now go to sleep." Brenda nodded at the couch in the corner, before leaving the room. "You don't want to fuck up your next job."

Ranger lay down on the lumpy couch. He slowly became unconscious, curled like an infant, with stubble on his face. Ranger would be sixteen in a month. He would never leave Brenda again, and she would never again hire any other boy.