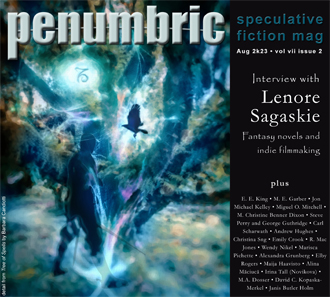

The Macaw

by

Steve Perry and George Guthridge

previous next

Admired

Charmer

The Macaw

by

Steve Perry and George Guthridge

previous

Admired

next

Charmer

The Macaw

by

Steve Perry and George Guthridge

previous next

Admired

Charmer

previous

Admired

next

Charmer

The Macaw

by Steve Perry and George Guthridge

The Macaw

by Steve Perry and George Guthridge

Aleem’s entrance into the Indian ambassador’s party was as smooth as oil on warm glass, at the precise instant between too early and too late. That was part of the showing, in itself as important as any other part. She glided in quietly, the twin tigers padding along beside her. Then she stood posed, not speaking as the door slid shut, blocking out the L.A. night and the ever-present crowd that must have watched in awe as she’d alighted from her private car.

Next to me, the ambassador had lifted a drink bulb to his lips. He choked and covered his mouth with his dark hand when he saw her. Saw them. He hadn’t approved the tigers’ use, I realized. Someone in his government had surprised him, someone who knew how much more valuable the rare cats would be after Aleem used them in the showing. In her art.

Aleem was dressed in a gray bodysuit and ballet slippers, her thin figure almost childlike. Her short, ash-colored hair covered her head like a cap, and she kept her face carefully neutral. In the dimly lit room, she was nearly invisible between the tigers, as she had intended.

But the tigers—ah!—the tigers!

They were Royal Bengals, psychotopicked to follow commands from the ultrasonic stimulator Aleem carried hidden in one hand. As the crowd stood breathless, the moment stretched to a fine and calculated tension—the anticipation building ...

The animals paced away from the slight woman, moving in unison toward the large oval rug near the bar. The crowd parted in a rippling wave, uncertain how to react. It was safe, wasn’t it?

The big cats surveyed the room, yawned, and stretched out as if lordly aware they were the center of attention and admiration. Each was dyed with luminous green pulse-paint. Over that, Aleem had traced a line drawing of the natural fur markings in translucent orange and black. She’d timed the pulse-paint so the cats blinked sequentially, great beasts of living neon. The watchers had to shift their gazes from animal to animal, the effect nearly hypnotic.

There was more: Aleem had injected the cats with myelinglow and, wearing Kirlian shatter-glasses, had traced their nervous systems with yet a differently timed pulse-paint. The tigers were living blinking paintings, airbrushed to perfection, spectacular to behold. Once the media were allowed into the party, the yawning beasts would show up on a billion holoproj sets around the world, testimonials to the world’s most popular living painter: Aleem Van de Mar, screamingly successful artist.

And commercial whore.

And my wife.

The pulse-paint was organic, engineered of living microorganisms, and the bright colonies had brief lives. The colors would fade within hours. By then, holographers would have done their magic to capture and counterfeit the tigers. Three-dimensional projections would adorn private cubicles, and museums would have signed, limited-edition copies. But the living art would dim and be brushed away as flecks of dead gray paint, like dried moss in sunshine, leaving the tigers as before, though more famous.

Her work’s transience was one reason for its popularity. Some critics claimed it expressed life’s ephemerality. The more cynical said the value lay in the lack of an original—Aleem’s signature on signed copies was the real collector’s item, and people paid dearly for it.

I looked away from the cats and caught Aleem glancing at me. Her neutral expression flickered for an instant, and I thought I saw longing, fear, perhaps anger, in her face. Then the mask slid back into place. I sighed and nodded, wondering what she might have seen behind my own bland façade.

“Ah, Aleem!” Grinning, the ambassador stepped toward her, arms outstretched, to congratulate her. As well he might: His party was made. The showing would be talked about for months, and he would gain political clout in small but definite ways.

The many-headed creature that was the party rumbled and broke into approving voice, a cacophony of praise acknowledging Aleem’s latest triumph. I turned and worked my way through the throng, heading toward the sleep rooms. I could feel Aleem’s stare against the back of my neck, pressed there like a hot hand.

* * *

Most of the sleep rooms were empty. I picked one and entered, pausing only to jab the “Occupied” LCD button. I sprawled on the gel cushion and closed my eyes in the soundproofed room’s nearly tangible quiet. The soft red light faded out as I adjusted the sleeptrode mesh over my temples.

Sleep: needed for normal recharging and lately grown fashionable in high-density areas as a means of removing one’s self from the effects of overpopulation. Scientists had recently documented that the vibrational level of a city past optimum density levels of electrochemical beings—people—was unhealthy. It was a constant stress, invisible, but as real as wind or smog. Want to add ten years to your life? Sleep more. No need to feel guilty about sacking out. Enjoy the deep slumber that sleeptrode pulse-units offered.

Lately I used sleep for yet another reason.

To remove myself ... from myself.

* * *

Within a warm fog, a buzzer scolded me.

I blinked. The dim light of the sleep room was on. I rolled over, not yet fully awake. Sleep’s small death released me reluctantly, leaving me without dreams to mark my passage back into life.

I had almost never dreamed, at least not dreams I could recall upon awakening, since I’d stopped writing and started using the sleeptrodes heavily. Jerrod the poet, once sought after by publishers and generally commended by critics, no longer had dreams to commit upon his public. My time had passed. The spark had drowned—who knew that I had poured water on it myself? I had climbed an artistic mountain—and leaped off.

It wasn’t Aleem’s fault. I had gotten to the end of my song. That was all. As she was coming to the end of her song.

“Jerrod?”

Aleem was outside. She’d come looking for me. I nodded to myself. I had something she needed.

“Come in.”

She eased inside, followed by the party’s noise, and shut the door. I glanced at the room’s chronometer. I’d been asleep only a couple of hours. Nearly 2400, the witching hour.

The thick quiet came back. She settled on the end of the cushion, and for a moment we looked silently at each other. I drew up my feet and sat cross-legged. The gel gently undulated.

“You’re missing your party,” I said at last.

She shook her head. “You know what I think of those ... people.”

“It’s a zoo out there.”

“You’re not funny, Jerrod.”

“I know. I wasn’t trying to be.”

She touched my knee. Her fingers were long and slim and delicate-looking, the first thing I’d noticed about her all those years ago. She looked sallow-cheeked in the weak light. Her eyes brimmed with tears. “I know what you think of the showing,” she said. “But one of us has to work. The residual rights from the tigers will—”

“—keep us fed and housed much better than my poetry,” I finished. “As did the residuals to the chimp and the piranha and that stupid, ungrateful toucan—”

“Jerrod ...”

I shut up. We were slipping into that old hateful dance, its choreography too familiar, almost boring for all its internal violence. I’d tell her the money wasn’t important. We could live without it; and if only—She’d say I couldn’t understand any longer. I had given up that right. And if only—

The fight had been good the first time, alive and raw, and we’d made love afterward in our haste to reconnect ourselves. But the fight had long since become etched into dusty, mindless grooves. Always it seemed we started with better intentions, hoping somehow to exorcise our demons, but it never went that way. The troops were entrenched too deeply. She had sold out. I had given up. Somewhere, somehow, we had lost everything. Each of us; and both of us.

“It ... it was a good showing, wasn’t it, Jerrod?”

The ritual question. And my answer, the one she had to have, the one small thing I could still give her: “The tigers were the best yet. I mean that.” And they were—for what they were. More complex than the chimp or piranha or toucan, the tigers were better; not risky, not art, but excellent craftsmanship. She had discovered the formula her public would nurse on for as long as she wanted.

She nodded, put her head in her hands, and began crying. We were helpless together now. There was nothing I could say or do for either of us. I stepped from the now-oppressive silence into the babble of the party, leaving Aleem behind.

The party saddened and angered me even further. Couples and threesomes rutted in various forms of sexual activity on cushions and the rug. The curtains had been thrown open to the L.A. lights. The bulletproof glass kept out the city’s accepted violence and suffocating, overcrowded chaos, the spin addicts and eight-year-old prostitutes and gangs willing to kill for black-market kidneys.

It kept in the terror of feeling lonely in a crowd.

Naked as a newborn, the ambassador staggered past me, waving the ultrasonic stimulator and grinning at the tigers, his electronic birthday present. A statuesque blonde gowned in glittersilks touched my shoulder and smiled. He/she was a morpho conversion, able to please with whatever genitals one might desire, but I turned away. I didn’t want to be distracted by sex. I wanted the silence of a crematorium or a walk alone in cold acid rain. Quite the martyr.

I made my way past the animals, all the animals, to the bar. The tender suggested smoke, capsules, or needles, but settled for a drink the ambassador had had created especially for the party: an orange-on-orange mixture with the too-cute name of Annie’s Amphetamine Antidote. It came in a pair of bulbs. The tender said you really shouldn’t have one without the other.

Like certain tigers.

* * *

Two months passed, a listless time suffused with ennui. Aleem and I seldom saw each other. When we did, I made small talk about how I might fly up and see my dad, but I never packed. She spoke of a new curry she intended to cook. She never cooked it. She hated cooking. Neither of us mentioned tigers. During those rare times when one of us felt desire and tenderness, the other never seemed to. We spent most of our time in our penthouse in the quakeproof high-rise that jutted above the heavier ground smoke, and in our own rooms. Me in the bedroom, with the ’trodes. She in her studio, with whatever new animal masterpiece she’d undertaken.

On the evening of Aleem’s next show, I heard crying from behind her door. I didn’t know what she was working on. There’d been no cheeps or barks, and she never allowed anyone to view a work in progress. I hadn’t seen her in four days. The quiet sobbing was like that of a child huddling in a closet after being punished for something she didn’t do. Paradoxically, the sound triggered a memory of a time without tears. Standing outside the plastic door of her studio, I remembered our laughter when we’d visited the Mato Grosso and the Mbaya Indians—and saw the macaw.

* * *

We had been young and twenty then, and answers were simple because questions were simple. Aleem was just out of CalArt, and I was flunking med school. We had little money and no prospects, just each other and a passion for art. We spent the summer living in the tiny apartment I’d constructed in the barn loft of my father’s dairy near the base of Washington’s Mount Adams. Between writing and painting and lovemaking, I helped Dad run the milkers while Aleem cooked—yes, cooked!—and canned and picked berries and exulted in the greenery and clean air. We were happy and stupid and in love, and we told each other we had it all; we had the world by the tail.

In the fall, we returned to L.A. so I could give med school a final try. We could always reboard the shuttle, we assured ourselves. Washington would always be there. Somehow, on a lark, we ended up heading to Brazil, to photograph hawkmoths and parrots and naked natives. Our cameras, though, were loaded with more than holoplates: I stole a few grams of the new drug, myelinglow, from my chem lab. It was being tested for visualization of nerve tissue. Though the drug could produce intense pain if not countered by chemical or electrical means, it was also psychoactive and psychedelic, and we had heard Brazil’s Mbaya Indians used a cruder form of it in their religious ceremonies. The Indians, it was said, would pay almost anything for the pure stuff. We figured to take it up the Cuiabá River to trade for organic cocaine and mushroom dust and animistic art.

The Mbaya had ruled much of Brazil’s interior centuries ago, keeping slaves and considering the conquering Portuguese unworthy of trade or even talk. Most remaining tribal members now lived in squalid towns bordering the bush. They sat on the dirt floors of their prefab huts and drank maté and watched the holoproj and rarely talked of awyu, the spirit of life.

Sometimes, though, as when someone smuggled in myelinglow, they slipped into the forest. There, in the old village, they danced and dreamed.

* * *

The jungle air was humid, a dense medium that hung like damp smoke amid the quebracho and soviera trees.

Sunlight that managed to break through the forest canopy seeped through the palm roof of the biatemannageo—the communal house—and dappled the native dancers. Reddened with urucu clay, they moved counterclockwise step and step, following the soft, lilting chant they all droned. Aleem and I lay naked together, stoked on the myelinglow the Mbaya shared with us and stoned on the barbiturate vapors we used to ward off pain. Wearing crude Kirlian shatter-glasses the Indians made of jacu shells treated with rare organic earth and phosphor compounds, we watched the dancers’ nervous systems flicker and spark, a dazzling nervebeat dance Aleem was later to translate and commercialize with her pulse-painted skin tracings on animals.

The Indians grinned and reached for us. Trippy, we jumped to join them, their electric dances and ecstatic dreams spiraling us down to pleasant exhaustion. Then we sprawled on the ground outside the communal center. We watched spider-limbed coata monkeys chatter among the lianas and tendrilled vines overhead. Under the drug’s spell, we felt a thirdness between ourselves that went beyond simple synergy. Aleem would speak, and the words would appear as a thread between her lips, but I would have already sensed her thoughts, primary colors, that clicked and squawked on a branch above us, watching me as I watched him.

“Other people need to ... see this, Jerrod.”

I watched an insect crawl across her stomach.

“I have to show it to them! In my art!”

I nodded. “But when we come down, you’ll have ... forgotten.” The words, hard to push out, seemed useless and misleading. “The colors will dull, go ... flat.”

She turned toward me, all warmth and flesh. I was filled with desire. “No, there’s a common de ... nominator,” she said, her words slurring. “Art, astronomy, philosophy, architecture—they’re all expressions of the ... same thing. Don’t you see?”

The sheen of sweat on her flesh fascinated me.

“It’s like the difference between the medieval worldview,” she went on. “Geocentrism, inductive reasoning, flat and one-dimensional paintings and cities without ... interior design and—that of—God, I can’t hold the thought; I’m losing it!”

I watched the shadows along her cheekbones and under her arms and shiny breasts break into shards as she ran her fingers through her long, ashen hair.

“And then ... then there was the heliocentric Renaissance with deduction and perspective and long avenues leading to the gardens of Versailles. Can’t you understand, Jerrod?”

I lay my head in her lap and looked up at her face. “I love you.”

She slid her fingers into my hair and smiled and kept talking. “Then, let’s see ... the nineteenth century. Structured. Steel girders and Spencer and Darwin—” She squinted, as if to see the idea better. “Then cubism and Einstein and skyscrapers with entrances but no front doors. The multisided universe. It all connects, Jerrod!”

I kissed her belly.

“Aren’t you listening to me?” Her eyes seemed so clear and wide I could drown in them.

“You don’t need to tell me in words.” I had to force the words out. “Thinking and art change together. So as an artist, you need to discover how things fit, and flow with them—right?”

She took my face in her hands. “No, Jerrod—lead. That’s what an artist does ... leads.”

I knew that. I nodded.

The macaw laughed so hard he lost his perch and had to flutter to another branch. A feathered rainbow in the hot, diluted light.

* * *

The memory faded. I was staring sadly through our hallway’s partially polarized window, down at the sad gray city, and listening to Aleem sob in her room. We had come too far since those days in Brazil, I realized. Not just Aleem and I—all of us. There seemed no room for art in a world where people did little but sleep, eat, use one another, and—

Yet another cry.

“Aleem?”

She didn’t answer.

“Aleem!”

“Go away Jerrod.” I could hear the pain in her voice.

“I won’t. Open the door.”

Quiet again, save for the soft crying.

“Open up, or I’ll kick the damn thing down!”

After a time, the latch hummed. The door slid open, and she stood staring vacantly at me.

I wasn’t ready for what I saw.

She had depilated her entire body—head, crotch, axillae—and was erotically, hairlessly nude, except for the pulse-paint, which throbbed with a rhythm equal to her heartbeat. Her head was egg-smooth, even the brows and lashes gone. Her art was her only adornment. My anatomy lessons came rushing back: red higher brain, blue medulla oblongata and cervical, blue thoracic, red lumbar, ending in a blue-tipped filium terminale. Each pair of spinal nerves alternated likewise.

She’d also somehow managed to trace her peripheral nervous system. Hundreds and hundreds of lines decreased in size until they were hair-fine, a nearly invisible netting, from back to pulsing front.

I stepped back, startled, and the red and blue blended to purple with the extra distance.

It was incredible.

“I didn’t want you to see it,” she said. “Not yet.” Her voice was strained, as if the words had trouble passing through the mesh of color that covered her lips. “But I don’t know if I ... if I can make it to the showing. I feel so tired ...”

Her eyes rolled up into their glowing sockets, and her knees buckled. I lurched forward and caught her as she collapsed, and her weight pulled us back into her studio. I struggled to drag her to the couch, kicking aside expended hypostat tubes and paint-smeared towels. As I lay her down, the paint pulses began speeding up, going much too fast.

Aleem!

She gasped, her face distorted by more than paint. I realized what must have happened. The myelinglow would have caused her tremendous pain, especially with the doses she’d need to keep taking to paint herself. She’d been popping painkillers along with the myelinglow so she could work. Either she’d overdosed, or the combination of chemicals had thrown her system out of whack.

Her eyes fluttered open. “I had to trigger it for you, Jerrod. I know what you think of my work, but I had to—”

“It’s all right. Easy now.”

Her face was pale where I could see it beneath the paint. Her skin felt clammy, and her pulse was rapid and thready. Even a med-school failure could recognize shock.

I propped her feet on a pillow and pulled the pink chenille cover from the back of the couch over her. I punched in the emergency code on her phone, babbled that I needed stat medical help, and started rubbing her arms and legs, trying to circulate the blood.

Far in the back of my mind, I heard something from a South American jungle, laughing at me.

Don’t die Aleem. We haven’t yet finished paving the road to Hell.

* * *

She came home five days later. She was polite and quiet, but there was something different about her. I couldn’t tell what it was, and she wasn’t disposed to tell me about it. The brief connection we’d had when I’d thought she was dying was gone.

That night, in my room, the sleeptrodes dangled over my bed like the pincers of a malevolent crab. The headset’s platinum mesh looked alive. I could hear it calling: Sleep, Jerrod. Let it all go. Forget. Sleep.

I reached for them, with their easy, dreamless answers.

And remembered Aleem pulsing nakedly, dying.

I turned away from the sleep machinery. No. Not this time.

I walked across the hall and tapped on Aleem’s door.

“Listen,” I said, at a loss for the right words when she answered. I, the poet. “I—we have to—there’s got to be some way—” I waved my hands mutely, feeling like an idiot.

“I know.” She took my hands in hers and looked at me solemnly. “We have to go back.” As if that were possible.

I shook my head. Thomas Wolfe said it. You can’t go home— “I mean really go back,” she said. “To the jungle. It all changed there, Jerrod. Somehow we got part of it, but we missed something. I don’t know what. But something.”

After a moment, I nodded. Maybe she was right.

* * *

We flew in, rather than hydrocrafting up the Cuiabá. The once-lush jungle was a patchwork of logging operations and farmland. The Mbaya Reserve, when we found it, had shrunken to a small fraction of its former size. It featured air-conditioned huts for the tourists, complete with jaguar-skin rugs and mint maté in frosted glasses decorated with little green parasols. A concrete macaw as large as a house hulked above rides such as the Amazonian Fear Wheel and the Barrel O’Monkeys. Mustached boys in parrot-colored suits and girls wearing baskets of fake fruit on their heads sold tickets and trinkets. Dances were twice daily, the dancers fully clothed. No drugs, no shatter-glasses, no awyu. The grandsons of Disney had entered the jungle and given it a G-rating.

Aleem looked as sick as I felt. I thought about the ’trodes in my luggage and started toward the reception area. I’d get a room—and sleep.

Aleem grabbed my arm. “Come on!”

I stared at her. “Where?”

She helped me grab our stuff and led me to a dock where big plastic canoes were lined up. We rented one and puttered out into lagoon. “Aleem ...”

“Look for a stream. There’s bound to be something feeding this concrete pond.”

I looked. Eventually I spotted the feeder stream. A metal gate of wide mesh blocked the entrance to the fake lagoon. Aleem found a heavy plastic paddle in the bottom of the canoe, raised it over her head, and began smashing the small lock. She swung the paddle as if it were an ax and she were back on my father’s farm, in another life. There was a fury in her, a passion I hadn’t seen in years. The lock stood between her and escape.

After eight or ten blows, pieces of the green plastic flew off into the too-blue water, but Aleem kept hammering away. I could only watch, frozen by her passion.

The lock gave before the paddle did.

Aleem sat back, flushed and sweating, and dropped the ruined paddle into the bottom of the canoe.

I pulled the gate aside. It squealed in protest. I gunned the motor—we were through!

We didn’t speak, but I felt close to her.

We passed through kilometer after kilometer of narrow channels infested with swamp grass and gnats. We twisted the canoe around logs, down steamy passages, over lilies and thick scum. Finally the stream widened, and we came to a clearing with several collapsed huts in it. I pulled the canoe onto the shore and got out. It was twilight. Mosquitoes buzzed around us but didn’t alight—the canoe had a portable repeller, which we carried ashore. In the distance the lights of the park touched the gathering darkness. We were not as far away as we’d thought or hoped.

I sat on a log and stared at the destroyed huts.

“It’s the old village.” Aleem gazed at the tipped-down roofs of shriveled palm thatch and broken bamboo rafters. “There’s the biatemannageo.” She pointed. “It had aluminum casings where the poles fit together.”

“I didn’t think you remembered those days all that clearly, what with the drugs and all.”

“You don’t know me very well.”

“Maybe I don’t.” I felt like laughing bitterly. We were back but were different people—as different as the village. And perhaps as deteriorated.

She started propping up a roof for a lean-to. I watched for a while, then took out luggage from the canoe and started a small fire. We were staying by unvoiced consent.

We didn’t talk much as we worked, but whenever I looked at her she smiled. We rethatched the roof and raised it at an angle to shield us from the distant carnival lights. We picked plantains and dug cheebo root and boiled some of the mucky water to cook the plantains and make tea. We laid down part of the roof as ticking. That night, Aleem put a scarlet liana blossom in her hair and settled down beside me. “We’re back,” she said. Back together, I knew she meant. “Do you remember how it was then, how we danced? How we used the shatter-glasses to watch each other’s nervous systems? Wonderful. And I told myself, ‘If I can capture this in art, then surely I’ll have discovered our age’s common denominator, the symbol of a self-centered world.’ No one touches anymore. Not really. No one touches nature or each other. If I could show people that, by letting them view the nervebeats of animals and—” Her voice broke slightly. “—and finally of the artist herself—but I didn’t get it right, Jerrod. I know that now. All I got was easy repetition, without risk.”

I said nothing, and we lay looking up at the dark, moon-drenched foliage. “I think I’d like to try the ’trodes tonight,” she said at last, softly. “And I’d like you to try some myelinglow. A light dose, like the Mbaya used to take. Like we used to take.”

“I hope you’re kidding.”

“We’ve rarely experienced each other’s addiction. Maybe that’s been our trouble.”

If it would placate her, if it would help us—O.K.

Aleem used the ’trodes. As I waited for the injected myelinglow to take effect, I watched her restless sleep. She tossed and turned on the ticking, and I wondered if her ’trodes-spun slumber was dreamless, as mine always had been.

“Dancers!” I heard her mutter once.

Then the drug brought its bright dreams, wonderful splashes of color that swirled through the darkness, meaning everything and nothing. In the center of those reds and blues, I briefly envisioned Aleem emerge from a restored biatemannageo and walk toward me, a gold-and-honey twenty-year-old who was unselfconscious of her nude beauty. “I think I’ve found something, Jerrod.” She smiled as she spoke, the words serpentining from her mouth and winding up among the quebracho branches. “It has to do with the myelinglow. The Mbaya are vague about it. I can’t always follow what they’re saying for all the riddles and laughter, but it has to do with shared experience and dreams—”

Then I heard the squawking of a macaw and the gibbering of monkeys.

I opened my eyes. Aleem had hung an old fashioned 3-D easel from the corner of the lean-to and was busy with a holoproj painting. It was a smear of color, blues and greens intertwined with silvers. An abstract, and Aleem never painted abstracts.

She looked troubled, frowning at the painting. “You slept nearly fourteen hours.” She didn’t look at me, only at the picture.

“It’s the heat.”

She eyed the holo across the top of her aerosol brush, and suddenly her face flushed with anger. “Just not right! I thought I—Damn!” She threw down the brush and stalked off between the trees.

“Aleem?”

“Leave me alone, Jerrod. I mean it!”

That evening, she emerged from the jungle and returned to the easel. She pressed the recycler; the colors vibrated and were sucked into the easel’s base. She didn’t speak. Just stood staring at the blank screen.

I hooked up a ’trode set to our luggage’s power pac, turned the intensity to high, lay down on the ticking, and awaited oblivion ...

* * *

A macaw called from a tall tree whose fronds were swept-back scythes. I stood on spongy ground, my arms extended toward the bird. His rainbow wings beat the air slowly—oh so slowly!—and his talons released the limb as he rose through the gluey air. I wanted to speak to him, touch him, feel his feathers under my fingers. I yearned upward—

—and found myself in the trees, clutching the limb where the macaw had been. My hands slipped, and I hung upside down, my legs looped over another limb; I was a giant sloth.

—Monkeys gibbered around me. Jacus and japim burst cawing from the treetops.

—On the ground, mop-headed and urucu-reddened Mbaya yelled and waved their spears. Did they want me? The macaw? Maybe the monkeys?

—Rainbow bird returned and alighted on the limb by my knee. His big beak explored its shoulder, searching for lice. He preened, smoothing down feathers on his left wing. He had Aleem’s green eyes.

—With one hand, I reached for the macaw, lost my grip with my legs—

—Tumbled down through a star-speckled universe, lost, alone, desolate, despairing—

—Aleem caught me! She wore a rainbow-colored dress, and her green eyes glowed with supernal light. She swept us sideways, and we became a comet blazing through cobalt-blue skies. She smiled, and her face shattered into twinkling shards of diamond and ice and love—

* * *

“Jerrod.”

I blinked and saw Aleem standing over me. The sun was high, and she looked tired but never so alive.

“You dreamed,” she said.

I rubbed my eyes. “It was so real, so incredibly vivid!” I sat up. “I—I never dream on sleeptrodes.” I stared up at her as the second part of the question came to life. “How’d you know I dreamed? How could you?”

She knelt and turned up my forearm. A small red circle showed inside my elbow. The print of hypo-pop.

“Forgive me,” she said. “I had to do it.”

I shook my head, and she answered my unspoken question.

“Myelinglow.”

“All right. But—why?”

She pointed at the easel. The spun acrylics were still wet and glistening and—

It was the macaw.

My macaw, from my dream, perched in a quebracho tree.

Impossible!

“I dreamed that,” I said. I pointed at the holo. “That painting—triggered my dream?”

She shook her head.

“What, then!”

She was quivering, her gaze intent as she looked at the bird. “It’s the myelinglow. It allows you to share someone else’s dream. That’s why the Mbaya used it, not to watch the dancing nervous systems! We got caught up in the externals and missed the point. We assumed the mild hallucinations were just that, pleasant little drug dreams, and that the real artistic value was the viewing of the pretty lines of nerve tissue. How self-centered could we have been!” She sighed noisily. “It must be a kind of telepathy, perhaps strengthened by the participants seeing each other’s nerves. Like biofeedback, maybe. I don’t know. I know only that when I wore the ’trodes the night before last, I had a lucid dream. I knew I was dreaming—and I felt I was dreaming someone else’s dream.”

“You probably still have myelinglow in your system, as much as you shot up back in L.A.”

She nodded. “That’s what I figured, too. I got up and tried to paint what I was seeing, but I couldn’t sustain the images.” She glanced at the macaw and looked away angrily. “Then, last night, you opted for the ’trodes, and I realized that with a direct link, a second mesh tied into that of the sleeper, and the delta filtered out ...”

I stood and studied the macaw.

The implications began bubbling up in my brain.

“I took a small dose of the drug and let my mind blank, linked to your sleeping mind,” she said. “That’s what I saw. The macaw. And it’s ...”

Her voice filled with quiet horror.

“Oh my God.”

Her eyes suddenly looked as lifeless as the afternoon in her studio. I grabbed her by the shoulders and shook her. “What’s wrong!”

“It’s awful, Jerrod. The whole idea.” Her eyes welled with tears. “I wanted to share something with you, but it’s more than that. Can’t you see? I painted the bird, but it’s your macaw—your vision!”

Then I understood. If the painting wasn’t a fluke, if it could be repeated, then Aleem had discovered another, and even more dispiriting, art form symbolic of our self-centered age. By combining myelinglow with the sleeptrodes, an artist would be no more than an instrument to actualize the dreamer’s conception.

“People will swarm over the idea,” she said. “They’ll fall all over themselves to get their thoughts into paint. It’s just like the last time we were here, when we rushed back to L.A. so I could paint nervous systems—only to end up repeating myself and hating myself. I acted without thinking things through. I should never have hooked into your dream, Jerrod. I should never have painted that ... thing!”

I said nothing.

“Wipe it,” she said.

“Aleem ...” I looked at the painting. It was beautiful.

“Clean the damn thing off! We have to keep this to ourselves, Jerrod. No one must ever know.”

I reached for the tab on the easel control. In an instant the spun colors would blend and run back into the reservoir, to be reused again—

I saw it then.

The macaw had blue eyes. Blue, not green.

“I’m not going to do it.”

She moved toward the easel. “Then I will!”

Again I grabbed her. “Wait, look at the bird’s eyes!” Now I could see other differences from the macaw I’d dreamed. The colors weren’t quite the same, and the patterns and saber-shaped tail were different. “It is your vision!”

“Don’t be ridiculous.”

“My macaw had green eyes. And the tree had broader leaves. The sky, too—it was darker, and without that hint of reddish sunset. This bird is cleaner, sharper, much more than the one I saw. It’s yours as much as mine. It sprang from both of us.”

Aleem looked from the painting to me, and back again. “You’re sure?”

“Yes! Do you know what that means?”

She gazed at the macaw a long time, a look of hope growing in her eyes. She nodded, put her arms around my waist, and smiled.

Maybe it was the myelinglow, and I was being a dreamy optimist, but I decided that—at least for Aleem and me—the macaw symbolized more than a manifestation of a self-centered world. It was a reaction against it. No longer could viewers recline before their holoprojs and admire or criticize without seeing a work’s essence. Perhaps someday the artist and audience would no longer enjoy the easy freedom of separation. A painting might be a participation.

And the sleeptrodes coupled with myelinglow? What if that was an initial image for what the world sought and might soon realize: not self, but sharing? Perhaps civilization did indeed possess the hope, and the beginning of the capacity, to arrive where the Mbaya had come from.

My heart pounded with excitement. For the first time in years, I felt a desire to put words on paper for others to read. (An old art form, I know; but then, I felt older than when I had awakened.) Not the lifeless lines I’d been writing before I’d quit, but something squalling and squawking, imbued with energy and verve, precarious, out on a limb.

A poem in Aleem’s honor—but not for her art.

For us.

Words about a winged rainbow whose colors were blended.

And splendid.