Ytasha Womack.

Ytasha Womack is, amongst many other things, the author of the book

Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-fi and Fantasy Culture, which helped introduce me (and probably many others) to the larger Afrofuturist movement. But that work was published in 2013, and in the last several years Afrofuturism has definitely become a more mainstream concept. We were able to ask her about this recently, along with her thoughts on writing Afrofuturist works and the future of the concept.

I read your book from 2013. I'd like to ask a few questions about what has happened since then in Afrofuturism. In the last few years it seems to have sort of become more mainstream, more noticed. Would you say that has more to do with the film Black Panther

, or a sort of larger undercurrent ...?

Sure. It was a synergy of things happening. In the two-month period when my book came out, there was an art show at the Studio Museum of Harlem called The Shadow Took Shape, which is an Afrofuturist art show that received a lot of press. And there was also an Afrofuturism speculative fiction anthology that came out in that same period, which was the result of a KickStarter project. I think the synergy of that lent itself to a conversation, so within a day of my book coming out I think there was an article in both

Ebony magazine and io9.com. So

Ebony being symbolic of mainstream Black America, and io9 being this awesome scifi website ... so in that sense, in part the book, the art show, and this other book that came out started ... it's more a synergistic cresting maybe. A lot of things were taking place, some of which I wrote about. You know, the independent comic book creators, and the Black Age of Comics events, which were starting in Chicago, and they had one in Philadelphia and Atlanta, and so many Black indie creators being in just general Comic-Cons ... I think that was one dynamic that was really taking place, that shaped a lot, to be honest with you. In addition, [there was] the gallery art world, more artists sort of claiming Afrofuturism. ... Also, another thing that was taking place, that lead to the cresting, was the fact that science fiction was being taught in colleges. For most of science fiction's existence, it was sort of the sidebar of real literary works; now it's moving to the center, as were comics, which were increasingly being studied as part of pop culture and design. Hip-hop as design and aesthetic was being taught in college.

Ytasha Womack's book Afrofuturism: The World of Sci-fi and Fantasy Culture.

The first thing you do when you start looking at these science fiction works in colleges, it becomes obvious that it's using those to talk about the future, but they aren't highly diverse.

It was still all Asimov and ...

Right. Pretty much. And then it's like, who else is there? And that's when you start going to Octavia Butler, to Samuel Delaney, and a lot of the theory started becoming more of a conversation. But I think the book that I did on Afrofuturism really helped popularize the term, because a lot of the people working under the umbrella of Afrofutrist works were completely unfamiliar with the term.

Right. And as you say in your book, the term was originally from the '90s ...

It was from the '90s, but it was used more amongst some people in the academy, who were specifically writing about it as theory, and maybe used by people who were artists functioning more in the fine arts spaces. But some of your musicians or thinkers or people interested in philosophy, excited about history, Black history--they weren't using that term.

And after that, your book ...

It helped popularize it. And people could see themselves in it, because the way I wrote the book, you know, I wrote it from the perspective of people who were in visual arts, if you were into history, if you were more of a music person, if you were just trying to create change and help humanity, activism--there were different lanes in which people can see themselves, and they could think, I can really be into Afrofuturism, and I don't have to be a comic book [writer].

That was one of the things I liked about your book, was that each chapter talked about a different avenue. So, in terms of myths and archetypes, you talk about the need to explore beyond just Egyptian myths. Do you think that writers have been able to find other African mythologies that might have been missed out?

Well, sure. ... The fun thing about Afrofuturism is that you can pull from the past, you can pull from mythologies and the present and you can articulate futures, so there's a lot of remixing that takes place, in the same way that a DJ or someone pulling from samples of old soul cuts and jazz and mixing it with something that's very house, futuristic, and putting it all together, Afrofuturism does the same thing, and it's a pretty common process within cultural product by Black creators, particularly in the Americas, and this kind of constant quilting, pulling from these different narratives. Part of it, at least from the African Amercian standpoint, being Black in North and South America, we're descended from so many African cultures, sometimes with a conscious awareness of what they are, sometimes not with a conscious awareness of what they are, and so the cultures we're a part of are fundamentally these fabrics of different African cultures that under unusual circumstances have to merge. But even with that, there are still some very distinct themes that are uniquely African that you can trace directly to mythologies, to stories. And all of that to say, there's a lot of different mythologies. Whether one's pulling from the American South, or they're looking at ... I'll say almost "wisdom systems," from the African continent, because some of the things that some of us would want to call mythology are actually wisdom systems and beliefs that come out of ethnic groups, that are still working within those systems.

[So] yes, I think people are pulling from it, and they've been pulling from it. I think one of the reasons you see so much Egyptian imagery, references, in works that we call Afrofuturism is because there's an active reclaiming of Egypt as being African.

Right. When I was growing up that was almost considered more part of the Mediterranean, and so it was included with Greek myths and Roman myths.

Right, exactly. And so when you look at a lot of soul album covers, you look at someone like a Sun Ra, you look at Parliament-Funkadelic imagery, you look at Earth, Wind & Fire imagery, even pulling up to someone like Erykah Badu, who is very famous for wearing an ankh, and you take that even further, to just a lot of references in hip-hop and elsewhere among a lot of Black creators.

Egypt is referenced in part because in the Western world it's acknowledged that Egypt was an amazing great empire, and we are claiming that, yeah, it's a great empire but people you would today describe as Black were creators and instrumental in its shaping. ...

I think a lot of other wisdom systems are being pulled from. There's a lot of references to the Dogon because of their story about being descendants from the star Sirius B. There's a lot of reference to Yoruba culture, particularly because in the Americas you see Candomblé and what we call Santería as variations of the Yoruba spiritual system. So you'll see that in a lot of work. You'll see a lot of Akan references and works. ... This is from Western creators who are Black. And then I see a lot of references to ... sometimes the Dagara, I think because of Malidoma Patrice Somé, who has writings about the Dagara and, again, their wisdom system as well. So I do think there's a great interest in doing that. And then a great interest in people pulling from the spaces where they are. And then, I think among African creators ... a lot of African creators don't have to go above and beyond to make these commentaries because they're of the culture, and so it's more of an expression of where people are and articulating these visions to other people.

I guess I was thinking of Afrofuturism as African American ...

No ...

... but can it be purely African as well?

Covers of (left) Eartha 2198 and (right) Rayla 2212.

Well, Afrofuturism, the whole idea of people looking at the future and alternate realities through a Black cultural lens is, I mean ... all societies have a relationship with their future, a relationship with time and space even if it's not specifically articulated as the future. I think when Mark Dery wrote about Afrofuturism, when he sort of coined that phrase, he was thinking of it as being uniquely African American. I don't think of it in that way, and I don't think many people do. Now what can tend to happen of course is that if it's African American creators they're going to tend to write about futures from an African American lens, which can overlap but be different from a creator out of Senegal or a creator out of South Africa. The starting point might be different, but there are a lot of relationships and overlap. Nnedi Okorafor likes to use the term "Africanfuturism." She likes to talk about how she writes ... she uses that to describe her work, and she's distinctively writing from an African viewpoint that's not intersecting with the West at all.

When I'm talking about Afrofuturism, I think of it very much as a space with ideas about futurism, regardless of where you are in the world, if you're a person who describes themselves as Black or of African descent. In Brazil, they use the term Afrofuturismo, and they're writing about, again, futures and Afrofuturism, but it has more of a Brazilian framing.

Are there certain archetypes that kind of wind their way throughout Afrofuturism? I was particularly struck by the idea of time and timelessness, and you were also talking about past lives. I get the sense that your past life could be melded in such a way as to be in the future.

Yeah, completely. Afrofuturism looks at the future, past, and present often as being one. It differs from some other forms of futurism because there is a valuing of the divine feminine, or what we call the divine feminine, and that is a valuing of intuition and nature and their relationship. Intuition is viewed as being as valuable as your logical thinking in terms of informing your worldview. Afrofuturism differs in part because it does acknowledge that Blackness is very much a creation or technology, in the sense that race as we know it was created to justify the trans-Atlantic slave trade. ... It's usually not thought of in that way at all. I write about that in the book, this moment, when one of my instructors said which came first, racism or slavery, and we were just like, well, we're all arguing that racism came first, and she was like, no, there was slavery, and then the system was created to justify it. So when you keep saying that, it kind of upends things, upends the world.

Afrofuturism also values a lot of mysticism, these wisdom centers, as well as technology, so often you see an integration of the two in one form or another.

I saw as well you've spoken about its ability to kind of disorient you. Do you think that both Afrofuturism and speculative fiction in general still have that ability to move us from that comfortable space we all exist in and get you to move outside yourself and look at things in a new way?

Yeah, completely. A lot of Westernized thinking is based on sort of a uniform philosophy, and it's a uniform philosophy that's Euro-/ Euro-American-centric. Afrofuturism, just contemplating those ideas, takes people out of this thought process of intellectualism that we're all sort of socialized in, to say wait, there are other ways of thinking, there are other ways that people relate to the world, other ways that people integrate with space and time, which can be valuable in building a new take on humanity or connecting deeper to our own humanity. So just to express that in and of itself for some people is fundamentally shocking, because they're taught that some of these thought systems that we grow up with, that that's it, there is no other way of thinking.

Right, everything moves in a logical path and it goes here, to here, to here ...

Right. I did a talk recently on my Utopia Talks on IG Live that I've been doing each week, and what I'm about to do is talk about how so much Western thought is around binary thinking. You're either this or you're that; it's hot or it's cold; it's black or it's white ...

We get that with gender as well.

Right, completely. These things are positioned as being polar opposites, never as complements.

Yeah, which seems strange, because you almost can't have one without the other.

Right, which then goes back to the symbolism of the ankh and this balance. But it's usually not articulated that way, and so there isn't always this range for subtlety of discourse to some extent engaging other world thought processes. I think Afrofuturism is one lens into that, one lens of saying hey, there's other ways, other philosophical thoughts that come out of human experiences, and they're points to engage with.

Would you say the events of the last few years, which seem particularly concentrated in terms of protests and a sort of backlash to that, has that affected, or do you think that will affect, how Afrofuturist works will be created, or what they will be creating?

Well, I would say it would have to on one level, in the sense that people are shaped by a certain set of experiences, but in another way, because it is a building ... again, these protests are building on issues that people have been working on for centuries ... so, I think it has more to do with how people will choose to write about this time.

Can non-Black authors write Afrofuturist works?

Yeah, I think non-Black authors can. I think what's really important, though, is for people who want to write Afrofuturist works to really engage in the culture and be in dynamics where they are not in the majority. There's so many moments where people who aren't necessarily Black study or observe Black culture or might even engage with it, but they're engaging with it to some extent as an outsider and probably don't know it. So if you're growing up with pop and soul music, and you like

Black Panther ... these are all things you can easily like, and be a part of because it's a part of the fabric of where we are, but there's a cultural space that it comes out of, and that informs it. And that's the space that people need to sort of understand, in my opinion, if they want to write or create from. So it's not just an aesthetic, like you love ... say, you like hip-hop, and you say well, people are dancing like this, and they move like this, so now I'm hip-hop, right? [laughs] So the same thing with Afrofuturism; people can say, well, they say a couple mystical things about time, and, I don't know, wear something that kinda looks like Parliament-Funkadelic, and I'm quasi Janelle Monáe ... So, it's not just an aesthetic, it's not a costume, and it's not theories you observe. There's a cultural space, in terms of how people engage.

There's a story I tell sometimes about a guy I met once, and he wasn't Black, and he wanted to write Black characters in a steampunk project ... Black people from the late 1800s, and so forth, and I told him, I said that was cool, ... but do you engage with Black people today? You know, to get some sort of framing. Because oftentimes we don't realize that you're not really getting a full cultural insight. You hear interviews, you listen to music, you see people you think are pretty cool, but you need to be in spaces where you're not in the majority so you could get past whatever that issue could be, but you might not know what it is until you are in spaces on a regular basis where most of the people are Black. So you have to get past this lens of outsider/insider, you know, you're the observer looking at the observed, or whatever. You have to get to a space you can kind of see from the inside of that cultural lens, to the extent that you can. I think that that's important. And to be around a variety of Black people in different dynamics, from entertainment events to office parties to people's homes to holidays, or more everyday life, grocery stores [laughs], all kinds of things. A range of spaces. I think once people do this, they'll see how diverse Black cultures are. Even within the United States Black cultures are very diverse.

It's not a monolithic block.

Right. There's a lot of overlap, you know. But all of those things are part of a rich tapestry that help shape what we call Afrofuturism, and to get some sort of lens on that or relationship with it, I think is important.

What do you think the future of Afrofuturism is?

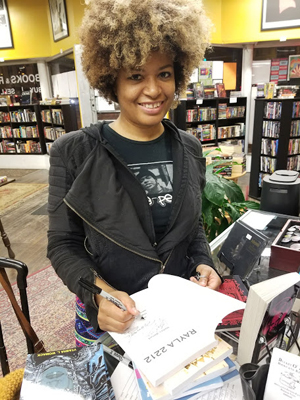

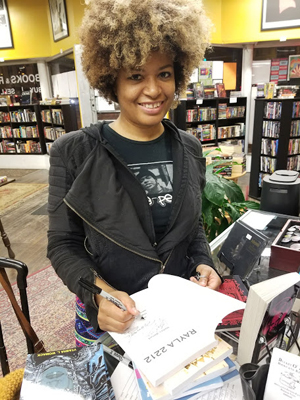

Ytasha Womack signing books at Bucket of Blood Bookstore in Chicago.

I think you'll see a lot of great storytelling, a lot of great film stories, a lot of work, way more cultural production, way more music, where people are using the term Afrofuturism and embracing those ideas and building on it. I think you'll see people trying to find ways to build on a lot of philosophical thought in organizations, in community planning, in design; I think you'll see more of that. And I think ... it will sort of highlight the Black cultures around the world and look at their relationship with them. Again, when people talk about Black people, they're not thinking about Black people as being global--being in the US, being in Kenya, being in Botswana and Jamaica and Trinidad and Brazil and England and France and in the Philippines. They're just not thinking of them in that way.

I was talking to someone about indigenous futurism, and they were talking about how the Black Lives Matter movement in Australia is in part showing solidarity with the experiences with the West but in part highlighting the challenges of aborigines in Australia. So there's a broader context for these ideas around Afrofuturism. Afrofuturism intersects with Black cultures around the world, but also liberation, technology, and mysticism, and the imagination--this idea of imagining, visioning the futures, the imagination of unusual circumstances, is really key [to get an] active part of how people live their lives in unusual circumstances, how they're able to push back, for us to be in the utopia that we're in today [laughs].

You can find Ytasha Womack at ytashawomack.com and on Instagram at @ysolstar. Her Utopia Talks take place every Tuesday on IG Live at 7pm CST.