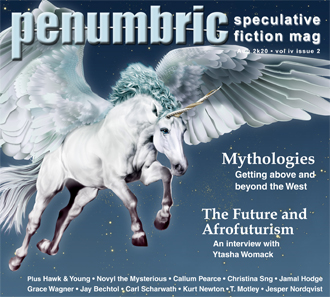

Unless you get your ideas from Harlan Ellison's Schenectady idea service, you are constantly on the lookout for story ideas, even subconsciously. (And even if your ideas arrive overnight using that particular service, you probably need to find some new ideas--it's a bit ... old.) You're also hoping not to write the same stories everyone else is writing (unless you're Hollywood; then that's your Holy Method). But to avoid the tendency to write yet another Tolkien-esque fantasy romp with the usual elves, or yet another aliens invade story, or even yet another ghost story, it could help to do some exploration further afield than just the same old Universal monsters.

Not to say that Tolkien-esque doesn't work (it's worked for hundreds of high fantasy stories and series). But this is a very well-travelled road. At the very least, shouldn't we look at the myths and religions behind these stories, and then maybe take a deeper look in other parts of the world?

Isn't "mythology" just religion misspelled?

Often when people talk about myths and legends, they are (consciously or not) making assumptions about another culture's religious beliefs or systems--the assumption being that that culture's beliefs are patently untrue. When speaking of civilizations that are no longer extant, or that have changed radically since their origins, this receives little criticism. To call the Greek stories of Zeus, Hades, Herakles, Athena, and so forth myths and legends does not rouse much anger. But when this is also applied to extant religions, there is a problem.

In this article we're talking about the stories of many cultures, across many times and places, whether they are meant as truth or parable, whether mythic or religious, as inspiration for our own writing. While I do use the terms myth or mythology to reference some of these stories, I mean it more to separate the idea of the mythic archetype from stories as we think of them today. More often, I try to use the word "story" with a surrounding context, or "religious story." I am making no judgment about what is real and what is not; that's not the point here, regardless. We should respect all cultures and cultural heritages, which leads me into a second, related point.

I reject terminology that indicates one is "using" these ancient tales, or "mining" the mythologies of old for modern ideas. These words not only indicate a sort of denigration and lack of respect for the source material, but also imply that, as a writer, you're not really immersing yourself in (or really researching) the culture whose stories are inspiring you; indeed, you run the risk of just appropriating another culture. In an ideal world, there should be more depth than just having read about Prometheus, or Thor, or Afrofuturism, or even Hansel and Gretel or stories of little mermaids. Even if this background doesn't appear explicitly in your piece, it will lend more dimension to your whole work. And it may change your whole outlook on life.

Note: We are not saying you should "use" other peoples or cultures in your work, nor that you should "mine" them--these are terrible turns of phrase that border on the appropriative. But your stories can be enriched, if you are willing to do the exploration (or better yet to live within the cultures--see our interview with Ytasha Womack later in this issue). And you can end up enriching not only your own work, but the genre in which you are writing, and indeed fiction generally.

That's some lofty goal, that. And it's much too vast for a primer like this to cover in a few thousand words (unless I've suddenly acquired the ability to write Zen koans in amongst all my parentheticals, and I can assure you I have not). But let's take a few small steps. First, we'll look at the kinds of stories one can look to for inspiration. Then we'll visit the broader world of archetypes, and finish with a bit of philosophy.

The Stories

First, a note. Although by necessity (or limitation) these stories and cultural experiences are presented as something of a list, they obviously are not "mine" to guide you through; indeed, I fear that this will come across as though I am leading one cultural group through a tour of Disney's "It's a Small World," as though we are only just discovering these other cultures (and "discovering" being such a colonial way of putting it). What I am trying to do is show that these cultural spaces are part of our general heritage as human beings, and that writing fiction from only one perspective is limiting. Please keep that in mind. Also, although I talk about "myths" and "stories," many of these are lived experiences, all deserving of respect; see the sidebar "Isn't ‘mythology' just religion misspelled?" for more on this.

And no myth or religious story should just be repeated verbatim. For instance, Tolkien's works are heavy with mythic influence: The Old English story of Beowulf had a massive influence, including the naming of elves, ents, and orcs (and, well, does Smaug remind you of anything in Beowulf?). The tales of the Norse gods and old Norse collections like the Völsunga saga definitely influenced Tolkien's stories of Middle Earth (as they did Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen). The Finnish epic poem Kalevala also bears some resemblance to the goings-on in Middle Earth, and Finnish was at least part of the inspiration for the Elvish tongue. And, well, whole books could be written about Tolkien's influences, possibly as long as his books themselves. But this is what they are: influences.

Note, however, that sometimes, with a twist or brought into modern times, a retelling can be successful. See, for example, Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman's

Good Omens, which tells a story the Bible doesn't quite get round to letting us in on. (Or, since I've gone and mentioned Harlan Ellison, try his story "The Deathbird" for another example of this.) And of course whole new tales can be woven using threads of the old; CS Lewis did this in The Chronicles of Narnia, and one of my favorite series as a child, The Chronicles of Prydain by Lloyd Alexander, was steeped in Celtic/Welsh stories. And for more up-to-the-moment examples, see even certain pieces in this months'

Penumbric.

But this is a very crowded space, especially if you're using Western mythologies and religions as your jumping-off place. Tolkien casts a very long shadow, and whole genres basically follow the same patterns. Christian stories, Norse sagas, Greek and Roman myths ... you may have to queue a long time at those particular wells to draw up much new water.

Where else can you go? There's literally and literarily a whole world out there ...

Below you'll find just the barest sampling, a stone skipping across non-Western mythology/folk stories/religious stories. I don't pretend to know everything about these stories, nor what they mean to the cultures that created them (but if I were to write about them, I would

need to be immersed in just that kind of way). And note again that these are ancient civilizations, as deserving of their own point of view as any in the West; there is far more to them than can be alluded to in a few paragraphs. But as even just the tiniest of samples ...

Africa

Let's begin in Egypt. Egyptian mythology is rich ... and has been used by Western writers to the point that it's almost no longer Egyptian, really, but more a general construct of the mysterious, a place from whence ancient curses hound our plucky adventurers, and treasures galore and the secrets of life and death are kept. (Which follows Western colonization patterns ... the Americas were once that mysterious place, where supposed cities of gold could be found [and plundered], where the fountain of youth resided ...). But Egyptian civilization and culture has begun to be reclaimed by African and African American writers; see again our Ytasha Womack interview on Afrofuturism.

The rest of Africa also contains civilizations and cultures with deep histories and stories and lived religions (and Womack's term "wisdom systems," which I love), such as the Dogon, the Yoruba, and the Dagara. These cultures have very different ways of looking at time and people's connection to the world around us. Immerse yourself.

Japan

While there are many Western authors who feel pulled by Japanese stories (especially with the popularity of anime and a long-running love of samurai and ninja and so forth), try something a little less well-known from that ancient culture. You may know of the Shinto deity Amaterasu, goddess of the sun, but what of her father, Izanagi, who along with his sister Izanumi begat the lands of the world and the deities who would inhabit them? What about Susanoo, god of storms, who is at various times impetuous and heroic, or Bishamonten, god of war? There are many stories told around these figures. If you don't know it already, you will find many anime that jump off from these stories ... and some of these are very good ways to examine the relationship between the religious stories and the more modern cultural output.

Chinese cover of The Classic of Mountains and Seas

China

I must admit I am more familiar with Chinese folk tales that have been made into films than I am with the literature, and indeed these stories have given more and more Western directors ... um ... inspiration, especially as Hong Kong cinema and stars crossed over into the West from the 1980s onwards with films like

The Bride with White Hair, A Chinese Ghost Story, Mr Vampire, and many others.

As in Africa, to speak of "Chinese" religious stories is to lump together many different regional cultures and their beliefs. The most extensive work I know of covering these is

The Classic of Mountains and Seas, which contains many stories while sometimes reading like a geography lesson. Also see the much more recent A Journey to the West, which while based on a true story also contains the story of the Monkey King and other deities.

The ancient stories have also mixed and interacted over time with Taoism, Conficianism, and Buddhism, taking on the cultural values espoused by these systems.

India

India is birthplace of both Hinduism and Buddhism (and others), and has a history of rich storytelling. From the Mahabharata to the Bhagavad Ghita to Buddha, these stories give us a very different version of life and death, of striving and not striving, of reaching enlightenment and escaping the world of reincarnation.

My own introduction to any of this was a small book of Zen koans given me by a girlfriend in high school (and yes, I know Zen Buddhism is Japanese). This lead me into deeper explorations of Buddhism and reincarnation and, really, into all of my religious studies. In the West, it has been difficult sometimes to divorce Indian thought systems from a very Westernized version sometimes thought of derisively as "New Age." I've actually found the Westernized adaptations useful, but again, delving into the originals is much more ... er ... enlightening.

Indigenous or First Peoples

These stories and cultures are often subsumed in stories of Western settlement and colonialism--as are many aboriginal or first people's tales. Growing up in the American West, I was fascinated by stories of shapeshifting tricksters, of spirit animals--but I was also presented all of these tales from the point of view of the dominant culture, and even now it appears that many of the collections of these stories are curated by non-native editors.

The stories themselves are diverse and descriptive and deserving of immersion. And, as with other groups that we sometimes think of as a monolithic block, there are many different tribes and many different wisdom systems.

Just knowing these myths/stories is a great starting point--but just that, a starting point. If you've read many of them across different cultures, you may have been struck by similarities in terms of themes, ideas, and even events. Welcome to the world of archetypes.

Jung, Campbell, and Archetypes

Your story doesn't have to be a twist on Jason and the Argonauts, or about how Fenrir the wolf came to dinner just before going out to devour the sun. It can use archetypes--events, characters, or motifs seen in stories across cultures. There are character archetypes like the wise old man (say, Morpheus in

The Matrix, vis à vis his relationship to Neo), wise old woman (the Oracle in

The Matrix, in her relationship to everyone), the Trickster, and the Hero; and creation, flood, and destruction (apocalypse) events. Carl Jung wrote extensively about archetypes and what he called the "collective unconscious" as a set of symbols existing in similar form in all human minds. Joseph Campbell applied these ideas to the myths he examined across many cultures. He thought of mythology as the "song of the universe"--taking Jung's collective unconscious into the realm of storytelling, like societies telling the world of their dreams (see

Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth, ep. 1). Campbell is most famous (and perhaps infamous, in some quarters) for his study of the "Hero's Journey."

Star Wars is a pretty basic example, like reading Campbell and plotting out the whole story from that: wise old man calls our hero to adventure, the hero refuses the call, then is forced to do it anyway--Skywalker's journey is an absolutely prototypical hero's journey. Very basic, in fact ... but I don't need to tell you how much that story resonated with audiences.

Other theories of this monomythic journey have arisen since, as there are issues with how masculine it is, how privileged it is, and even its unspecificity. But Campbell didn't write only of the hero's journey. He wrote extensively about a primary difference in focus between West and East--in broad terms, in the West, the focus tends to be on the God outside of oneself, whereas in the Eastern traditions the God is within. (A horrible mistake would be to think this is saying that any one of us is more godly than the others, which just recreates the hierarchy all over again; we are in this way of thinking each one of us god, or perhaps an equal part of god.) While this isn't as clear a distinction as it first appears (e.g., there are examples of Christian sects whose interpretation of Jesus's teachings sound more Eastern), rethinking our relationship with the divine can disrupt our typical mindsets, or do the same for a character in a story.

There are also differences in the ways even common archetypes interact with different cultural values. For example, the hero in the West typically reflects the values of individual performance and reward, whereas Eastern heroes often reflect cultures of teamwork. And yes, this example reeks of the stereotypical. But there are other examples. Say you're doing a story about destruction and death--how would your character approach this having been raised in a purely Western fashion (where your characters might believe they die and are then removed from the stage of the world) versus a character whose world view is steeped in the idea of reincarnation? These characters will probably react/act very differently to/in an apocalyptic situation, possibly changing the outcome of the entire story. And how would this work differently again in an Afrofuturist story, where ideas of time and space and past lives can be very different?

This extends to horror as well. While there are ghosts of some sort in many cultures, the idea of ghosts is approached in very different ways (but can be super scary regardless--see

The Ring for example). The reasons these ghosts have for being around, even, is different, which makes for very different stories overall. Or vampires--Chinese vampires are very different from Dracula (they hop, for one thing). Or zombies ...

There is also the Jungian idea of the anima and animus--the male aspect of the female psyche, and the female aspect of the male psyche, respectively. Different cultures handle these ideas differently, with some taking a very rigid either/or, binary stance (you're either masculine or feminine) and being very uncomfortable with any sort of "other" that doesn't seem to fit (and trying to "fix" these persons so they can be placed into society's placeholders), while others are very accepting of the fluidity between anima and animus (as Campbell says in

Myths of Light: Eastern Metaphors of the Eternal, "... the body of perfection is androgyne--neither wholly male nor wholly female, but combining both" [36]). How characters in these different situations interact, either with each other within their own cultures or as emissaries between cultures, can be stories unto themselves.

But in some sense I am getting away from archetypes and more into cultural philosophies ...

Archetypes into Philosophies

Games such as Final Fantasy X contain stories based on religious or philosophical ideas. (© 2001–2004, 2013, 2014 SQUARE ENIX CO., LTD. All rights reserved. CHARACTER DESIGN: TETSUYA NOMURA)

The mythologies/religious stories are often stories that can act as a doorway into a deeper study of how a culture has developed, how it works, and how it thinks (or used to). This can be very, very different from Western ways of thought. And these can lead, again, not to an attempt to copy, but to being able to create a much deeper society and culture in your own prose/poetry/art. See, for example, the Dune series, wherein Frank Herbert created an entire set of societies, myths, histories, and philosophies. Or even video game stories, such as that in

Final Fantasy X.

If you look at a culture's philosophical roots and history, you will often get another look through a similar lens as that afforded by a culture's mythic and religious stories--and see where the rise of certain more modern myths takes place. For example, one cultural myth of America (the heroic individual saves the community, not asking for praise but often rewarded for the hard work done) rises in part from the Western philosophies of the Enlightenment, and from the long rise of individualism and continued stories of how reliance upon one's own hard work can help you not only to survive, but to thrive. This has become so ingrained in the American psyche that, for some, the very idea of social safety nets is spurned as weakness and decay, or (patriarchally) a sign of the country basically losing its "manhood." (That other Western countries haven't taken it this far further demonstrates that different cultural histories and philosophies have "built" very different ideas into even similar governmental systems.)

Different philosophies can also lead to entirely different narrative structures; for example, in the West we typically assume a "good" story will have conflict; indeed, in school I remember being taught to seek out the type of conflict in every story. These stories end when the conflict is resolved, often by one side "winning" in some way. But in the East, there are Kishōtenketsu--stories involving no Western-style conflict. Rooted in Taoism, these stories (or, originally, poems) end not by one side winning out but by finding ways for disparate elements to coexist.

Finally, religions themselves are, in part, vast philosophical systems; Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam each have massive philosophical underpinnings, debated and discussed over centuries of faith and followers and far too complex to be discussed here. If you are writing stories with characters who follow these religions, or even creating your own, you will need to immerse yourself much more deeply into their ideas and cultures to even approach authenticity.

* * *

This article has necessarily been a skipping-stone across a very vast pond, one which many of you will already have made at least some small journeys onto. But hopefully it has provided some inspiration for new tales of new worlds, extended from the cultures of which we are most familiar. It can be daunting, the idea that to write a short story one should do this much research, but it shouldn't be a one-and-done kind of thing; it should inspire far more than just a few thousand words. And this exploration is a kind of learning that can help you examine not only the lives of your characters, but your own as well. Which may be what we're doing anyway when we write.