M.W.I.

by

Pete Barnstrom

previous next

A Strange

A Thin Place

Country

M.W.I.

by

Pete Barnstrom

previous

A Strange

Country

next

A Thin Place

previous next

A Strange

A Thin Place

Country

previous

A Strange

Country

next

A Thin Place

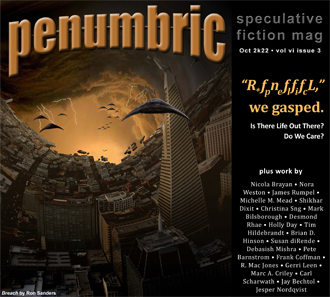

M.W.I. by Pete Barnstrom

M.W.I.

by Pete Barnstrom

Wayland rolled the paper into the typewriter, flexed thoughtful fingers over the keys, and then the door opened and a guy in a yellow work helmet said, “What the hell are you doing in here? Get your ass out!”

He seemed genuinely terrified, and Wayland told him that he'd just gotten in here, not a half-hour ago, but the hardhat guy said that he needed to get out now because the building's coming down, and Wayland said that seemed unlikely, but he packed up anyway, and that was Wayland's first clue that thirty years had passed.

At the curb, his typewriter under his arm, the sheet in it untouched, Wayland watched a demolition team driving heavy machines against the brick, and damned if the place wasn't coming down. How did this happen?

A sign in the rutted mud told him this was the future home of the Angus Byner Science Center. That made him laugh, just for the sheer impossibility of it. Angus, a lean and bearded grad student, had ushered him into the Time Box just minutes ago.

Or at least, he was beginning to realize, relative minutes ago.

Angus had called it the “Quantum Chamber,” because he was a bearded grad student who grew up on Carl Sagan instead of Dr. Seuss and didn't have any sense of fun. Wayland had instantly dubbed it the Time Box, and all the rest of the research team had joined in.

Mostly because it bugged Angus.

The idea was that time would progress at different rates inside and outside the box. The volunteer, a young and predictably starving literature studies scholar named Wayland Foy, would spend one year inside the box, but when he walked out, only one minute would have passed to the observers.

Both the shortest and the longest student project in the history of the physics department, Angus Byner liked to laugh. Not like Wayland and Vera had laughed at the whole concept in the privacy of her off-campus housing, but he laughed.

He found the address at the school library, and not long after, Wayland rang the bell of a respectable house near the campus. The door was answered by a fifty-something version of Angus Byner, still bearded, less lean, and it was only then that Wayland accepted that this might really not be the most beautifully elaborate prank ever executed.

“The resemblance is uncanny,” old Angus said, settling into a creaking leather armchair. Wayland didn't sit, instead pacing the worn Persian rug.

It was a nice room, this parlor, if only tenured professor-nice. Stuffy, a bit of dust, the glass shade under the ceiling fan was cracked. A small couch upholstered a lifetime ago, the fabric butt-shiny. There was a pipe in a heavy black ashtray, because of course there was, but it wasn't lit. The walls were lined with books, a lot of them, but not the crack-spined paperbacks that had once dominated the man's dorm room. The shelves weren't bungee- bound plastic milk crates, either.

“I've known Wayland for decades,” Angus said, “but I'd no idea he had a son.”

“I'm not his son,” Wayland began, then stopped. “My son, I mean. I am Wayland, Angus. And I don't mind telling you, I'm damned confused.”

Angus still had the same condescending chuckle he always had when explaining to the less-quick witted. “Yes, dear boy, you are confused. I know Wayland Foy. No one save his immediate family knows him better. And while I'll admit you do bear a striking similitude—”

“Similitude.” Wayland rolled his eyes. “Christ, Angus, did you never learn to stop talking like you're grading term papers?”

“It's Professor Byner, son. I do not appreciate such familiarity from students.”

“I'm not a student,” Wayland told him. “At least, I think the statute of limitations must've run out by now. My doctoral advisor has got to be dead, hasn't he? Old man Permutter still around?”

Angus raised his eyebrows, then lowered them. “Perlmutter? I haven't heard that name in many years.”

“It's me, Angus. Wayland. Just as I stepped into the Time Box an hour or so ago.”

Another self-satisfied chuckle. “Hour? More like thirty years—” and then his voice faded as the possibility hit him.

Wayland nodded. “Thirty years. That would explain why you appear to have put on a few decades.” He directed his gaze to the strained sweater-vest Angus wore. “And pounds.”

Angus caught himself sucking in his gut, then noticed and folded his hands across his midsection.

“The Time Box was supposed to allow me to age normally, but time outside would remain just where I left it. Wasn't that the theory?” Wayland leaned forward. “Your theory?”

Eyes wider, Angus murmured, “Oh my.”

“Didn't work, did it, Angus?” Wayland's fist tightened at his side. “Did you just leave me in there? What the hell, man?”

“Oh ... oh, Wayland.”

“Yeah, that's it.” Wayland resisted the urge to step forward, to slap that stupid, self- absorbed face. “Thirty years? That's a long time.”

Angus shook his head. “No. You're wrong.”

“Am I? Tell me how. Is it a joke? Tell me this is all a joke, Angus.” Wayland allowed himself to bring a hand up, point. “Tell me you had a barber thin you out on top. Tell me you've dyed that gray into your beard. Tell me that, Angus!”

“You don't understand.” Voice quiet now, Angus stood, walked to the mantle over a small fireplace, the hanging rack of iron tools tinkling as his pants-leg brushed against them. He reached for a framed photograph. “I didn't leave you there.”

He extended his hand, showed him the photo. “It worked.” Wayland looked, then took it, held it closer.

The picture was of the group, the whole research team, including Angus and Vera.

Champagne and smiles. They were gathered around a young man with a year's worth of hair and beard. A familiar young man.

It was him, Wayland Foy, scruffier, but otherwise exactly as he looked today. But it was thirty years ago.

* * *

“One minute for us was one year for you.”

It was Wayland sitting now, and Angus who paced. He stroked his beard, that affect he had when he wanted to let the world know that he was thinking and should not be disturbed. “You'd experienced a year's worth of hair growth, a beard. Your rations were depleted.

Despite provisions made for bathing, you, well, quite honestly, you stank.”

The photo was on Wayland's lap. He looked at it, traced the shape of his reproduced face, saw the faint reflection of his own face on the glass over it. Could it be a fake? Had he somehow not remembered this? “No.”

“Oh, yes,” Angus went on, thinking that word had been intended for him. “Your fingernails were trimmed, but we agreed that was necessary in order for you to write your novel.”

“Novel?” Wayland looked up. “Finished?”

“A year in isolation sharpened your resolve, I dare say. It was very well-received.” Angus nodded a smile at him. “Nobel Prize for Literature.”

“No kidding.”

“Of course it needs to be said,” Angus noted, “that its popularity was boosted by the success of my experiment. You became something of a celebrity. Some years back, Oprah did a week on you alone. It was the twentieth anniversary of the publication, now that I think on it.”

“Well, hot damn,” Wayland said, still looking at the photo. “What's an Oprah?” “Wayland, I don't think you're quite grasping the situation.”

“Oh, I'm quite grasping.” He looked up at Angus. “I'm just not quite believing.” “The world has changed.”

“Yeah, I noticed.” He'd tried to dismiss the billboards and cars that he'd seen on his walk here from the campus, centered as he was on finding Angus, figuring all this out. But he'd seen them.

“Technology, styles, social mores, everything you knew is different now.” “And what about me?” Wayland held up the framed photo. “Have I changed?”

Angus sat in the leather chair, across from him. “You must understand this. Wayland has lived a long and rich life in the time since then.” He lifted his chin at the photograph. “That's ... that's not you, not really.”

“Not me.” Wayland's eyes were unfocused, looking at something not in the room. “He's lived my life, but I haven't been here for any of it.”

“But now you have a chance,” Angus started. “You can have everything, anything you wanted, you can start anew—”

“It's not new for me, Angus.” Wayland's eyes were not unfocused now; he was looking directly at the older man. “I'm not old, like you. I'm not looking back at a life lived and wondering what I could have changed.”

He stood, tossed the framed picture onto Angus' lap. “What have I missed?” Angus hesitated. “Are you sure you want to know?”

“Shouldn't I already know?”

“Even ignoring world events,” Angus told him, “we're talking about thirty years of your, his personal history. Successes, failures, marriage, children ...”

“Marriage?”

* * *

He hadn't had to beat the address out of Angus, although he'd almost wanted to. The professor even loaned him a car. It only took Wayland a few minutes to realize he didn't need to put a key into anything to start it, but otherwise it was pretty much like the last car he'd driven. Yesterday. Or before he was born. He was losing track.

This house was in a better neighborhood, away from the city, with a lawn that rolled up to a facade that looked old and historic but wasn't. He left the car at the curb and walked to the door.

There was a man coming out, with a trim haircut and a suit. He carried a black bag. Did doctors make house calls again in the future? He said to Wayland, “Now's not a good time to call on your girlfriend, young man.”

Wayland walked into the house past him.

There was a foyer, with stairs going up, the floor polished. He caught sight of himself in a mirror by the door, and he wondered how he looked so young.

Voices came from up the stairs, a girl and a man.

“You think I'm a child, don't you? That's what this is all about!” “Dora, your mother needs you—”

“Don't bring her into this! You always use her as an excuse!”

Wayland thought he recognized the voices, but also didn't, knew he couldn't. He didn't know if he wanted to think about that at this moment, but he did know he couldn't confront those people, so he stepped past the staircase to a hallway with a door at the end. He could see tall metal tanks lined beside the door, brass nipples covered by color-coded rubber.

There was a machine inside, he could hear, something regular. Like a robot's heartbeat, or breath.

He pushed open the door.

There was a bed. Covered in some sort of transparent drape. Close to the window like it was, all he could see was silhouette. Unless he moved closer.

A woman. So old, but not really, not old, just—what? Shrunken? Pulled in?

She looked at him, and even under the mask over her face, he could see her eyes. They shone at him, happy. He could hear her voice over the mechanical respiration, just barely, hardly a voice at all.

She said, “Wayland.” He ran out of the room.

* * *

“Why didn't you tell me, Angus?”

Angus sighed. “Tell you what? That a woman you barely knew thirty years ago is dying? Vera doesn't know you, Wayland. She only knows what you've become.”

Pacing a groove into the old rug, Wayland shook his head, again and again. “You're wrong. She did know me. I saw her, she talked to me, spoke my name.”

“You were a hallucination,” Angus said. “All the drugs she's on, she's entitled to a phantasm from a happy past.” He watched Wayland pacing. “Frankly, even I'm not sure you're not an acid flashback.”

“What the hell happened to me?”

“As best I can tell,” Angus began, “we're looking at a literal manifestation of Everett's Many Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics.”

This stopped Wayland's pacing, if only for a moment. “M.W.I.,” Angus clarified, clarifying nothing.

“What is that?” Wayland's temper was frayed, and it was an effort for him not to shout.

Conscious of his wont for pontification, Angus took a breath, trying to simplify. “It's an extension of Schrodinger's Cat.”

Wayland closed his eyes. “That's not helping.”

“It's a famous critique of quantum physics.” Angus once taught first year science students, and tried to tone it down to that level. But those kids already had a grasp on the concept. Maybe it was part of the zeitgeist today? Or maybe those students hadn't been thrust into the position of being an example of the theory.

“The way Schrodinger saw it, if quantum physics was to be accepted unquestioningly, a cat inside a box could be either alive or dead, and was in fact both until the box was opened.”

“A cat.”

“Everett's Interpretation suggested that when the box was opened, there were then initiated two realities, two worlds spun off from that point. One in which the cat was alive and another in which it is dead.”

“Two realities.”

“Wayland Foy walked out of that room thirty years ago,” Angus said. “And, it would appear, he also did not.”

Wayland wondered which cat he was. The living or the dead.

* * *

He was in Angus' car the next morning as a young girl—maybe sixteen, seventeen, he found he couldn't judge such things anymore—walked out of Wayland Foy's house. Not his house. Another Wayland Foy, that's how he had to think of him, of all of it. This life was not his, no matter how much it seemed like it should be.

The girl got into a car and pulled away, and he hadn't thought he was here to see her, but young Wayland Foy found himself following.

Traffic was no different than once it was, people had not evolved into better drivers.

And teenage girls were no more attentive. She didn't seem to notice him behind her.

Other things were different, though. When did tattoo parlors go public? Right out there next to chiropractors and store-front law offices and some place that offered “paternity testing.” He saw children, high school age, he guessed, but with hair color he'd only seen in cartoons. And so many of them were huge, obese. Had they been trending that way when he was there? It was just a handful of years, it felt, but also long ago.

The girl's car did not stop at the high school. Was she older than he'd guessed? No, not compared to the kids he was seeing. Skipping.

He'd been a diffident student, grades good enough to get into the university, as long as his parents were paying, but he wasn't devoted. Still, he'd never skipped. Now he wished he had. So much time wasted in that building.

The teenage girl pulled her car into the shady parking garage of a shopping mall, and Wayland reflected that not everything had changed.

He nearly lost her in the mall, not because she was evading him, but because he got distracted by shop windows. Television sets bigger than the surface of a formal dining room table. Mannequins clad in bikinis made of less material than a pair of socks. A whole store devoted to Lego ... what he wouldn't have given when he was six.

The girl sat at a molded plastic table in the food court, looking at a pocket calculator and sipping from a styrofoam cup she'd filled from a nearby soda fountain. No one around to serve the drinks; could they be free? He wasn't thirsty.

“Aren't you supposed to be in school?” The words had just come out, without him thinking about it, and they made him feel old and stupid.

She looked up from her calculator and seeing her face hit him. He felt it just behind his ribs, like when he'd gotten the wind knocked out of him at soccer practice. He could see Vera's face, yes, but there was something in her eyes, the tilt, the attitude of them, that was someone else. He saw himself.

“Aren't you?” Her voice was teasing, playful. Nothing like the angry whine he'd heard up the stairs of her house.

“I'm not really sure where I'm supposed to be,” Wayland said, and the words were more revealing than he'd intended. He felt exposed.

The girl didn't notice. “Join the club.”

She pushed a sneaker at one of the other seats, and it swiveled on a hinge toward him.

He sat, grateful, thinking that if he hadn't, he might've fallen.

“I'm kind of ditching school,” she said, slitting her eyes back to the device in her hand. It wasn't a pocket calculator at all, he now saw, but something else. Were there no buttons?

“Kind of?”

She lifted her shoulders, just barely. “I'm also kind of suspended. But my old man doesn't know about it, so I'm going through the motions.”

Suspended? Was that not a big deal anymore? He didn't know how to ask. “Old man,” he said. “Your, uh, father.”

“Duh-yeah,” she snarked. “My father is an old man, you know?”

She was talking about him, but not. Wayland put a vertiginous hand on the table. Rigid, stable. He wasn't spinning. “What's he like?” he asked, hesitant. “Your old man.”

She didn't look up from the device. “I dunno. Like any other dad. He wants me to stay home right now. My mom's sick, and he has to go off and do some dumb thing.”

Leaving? With Vera ... the way he saw her? “He'd leave your mother when she's ... like that?”

She still didn't look up. “Yeah. He's kind of a dick like that. I hate him.” “Hate's a little strong,” he found himself saying, and now she did look up. She said, “What do you know about my dad?”

When her eyes were on him, Wayland felt the spin again. He had to turn his gaze away from her. “Nothing,” he said. “You're right. Sorry.”

“What's wrong with you?” she asked, leaning forward to examine him more closely. “You on the spectrum or something?”

Spectrum? “No, I don't think so.”

“Then what is it?” She actually put the device down now, watching him. “Why have you been looking at me like that?”

Like what? What had she seen in his eyes? “Nothing,” he said. “It's just ... I never even considered you before, you never even crossed my mind as a someday possibility, and yet ... now I'm seeing you for the first time, all grown and smart and funny and ...”

He stopped, suddenly aware that he was babbling.

She put out a hand, touched his where it gripped the table. “And what?”

His eyes felt wet, he thought, and he turned away. “It just ... it makes me happy.”

“Damn,” she said, but she didn't pull her hand away.

* * *

Her name was Eudora.

Wayland knew it as soon as she said it. In their weeks together, Vera had quoted Welty poems three or four times. They'd never discussed children, of course; he'd never even been aware that they could ever be serious enough to have a life together. He wondered how that happened. That's a memory he'd like to have. The thought of what he'd missed there put a knot into the muscles of his jaw.

They'd taken her car, a little Volkswagen that looked just enough like the ones he recognized for him to know that's what the designers had intended. She'd asked him if he wanted to see her house, and he'd said yes.

She never asked him his name.

Inside, he asked if her father was home, and Eudora giggled and he saw that she had braces on her teeth. She assured him that her father was out. He asked about her mother, and the girl told him not to worry, she was dead to the world.

Wayland looked down the hallway to the door with the tanks outside of it. Eudora pulled him another way, to the staircase and up.

There were windows up there, on the landing, and he could see the house was built around a small courtyard. He could see a bench outside, some plants in whiskey barrels, cut stubby and artificially rustic.

He saw Vera with a hand-spade and some colorful gloves, or he thought he did, just for a moment, turning soil, planting seeds. She wasn't there, of course she wasn't. Had she been interested in gardening? He didn't remember it, but he was now seeing how little he knew of her, seeing how much of her life, and his, had come after he left that damned white box. Was that it, what had done it? A year in there, kept away from her, had that made their union inevitable?

He could feel exactly how much he'd missed, and also not feel it. A phantom limb of his own past.

There was a photo on the wall, a wedding, bride and groom, was that him? His eyes couldn't quite focus, but he thought the man looked barely older than Wayland was now, and yet, so much older, more experienced. Where were the current pictures, when did he become not him, not the young man from the college, from the Time Box? When did he go from being a boy who thought he was a man to a man, a real adult with responsibilities? What had he missed?

Eudora pulled him to a room at the end of the upper floor's hallway. It was pink and there were stuffed animals and posters on the wall, some sort of group of smooth-faced Asian boys in white suits. Was this what pop music was now, what teenage girls were into? He realized he had no idea what teenage girls were into thirty years ago, either, or even when he was a teenage boy.

Another window, looking out onto the courtyard, and across from there was another room. That would have been the bedroom they used, he and Vera, and this room across the way for their daughter. Close enough to keep an eye on, far enough to give her some space to grow, an illusion of freedom, yes, that's how he'd handle it, being a parent. Let her be her own person.

Eudora pulled his shoulder and turned him away from the window. She pushed her mouth against his.

For just an instant, he kissed her, he was kissing Vera's lips, then pulled back. “Wait, hold on, I think I've given you the wrong impression.”

The girl pushed him against the wall to the left of the window and kissed him again, pushing her hands under his shirt. “No,” Wayland said, but he wasn't sure who he was saying it to.

“Quiet,” the girl said. One of her hands pressed against his face, pushing it against the window, and the other fumbled with the snap at his jeans. “You'll like this.”

Wayland looked down, into the courtyard, and he could see another window, this one under the landing to the stairs. The room under the stairs.

Vera looked at him from the other side of the glass. The mask shrouding her nose and mouth. Her eyes bright in her shrunken-skin face.

He looked at her, his wife of so many years, feeling the girl's tongue on his belly, biting, lower and lower. He felt calm.

He said her name, Vera, very softly, and she smiled up at him.

* * *

Wayland woke in semi-dark. He was in a girl's bedroom, a girl's bed, and the girl was snoring beside him. He shook his head. Can't think about this right now.

He slipped out of the room, finding his clothes, and tugged into his shirt as he got to the ground floor. He did not go out the front door.

She peered at him from the tented bed, smiling behind her mask. He stood inside the door, the ventilator's whoosh and click the only sound.

Wayland moved to her, touched her hand. The skin was paper.

Her lips moved behind the clear mask, and he moved his ear close. She said, “I'm glad you came back.”

“Vera, I ...”

“Hush. I can't talk long.” Her cool fingers tightened on his. “Just hold my hand.”

They sat there like that awhile, Vera and Wayland. He was exactly as she wanted him to be, and she was all he'd hoped she would be, all he'd never seen of her.

She said, “I've missed you.”

And he said, “I'm sorry I wasn't here.”

* * *

“Send me back.”

Wayland pushed past Angus into the house. “What?”

“I have to go back, Angus. I need to have what I missed.”

The older man shook his head. “Wayland, you have to know that's not possible.” “None of this is possible,” Wayland snapped at him. “It's not fair. I missed it all.

Everything! I deserve to have it back.”

“It's not a time machine,” Angus said. “It was a fluke, just a crazy, once-in-a-lifetime phenomenon.”

Wayland grabbed Angus by the sweater-vest. “It's not fair, I tell you. I can't be presented with all of this and not know how it got here. I don't even know why I married her, Angus, do you know that? I don't even get to remember who she was!”

“Wayland, you're hurting me.”

“It doesn't work this way. None of it works this way!” He pushed Angus onto the little couch, but didn't let go of the vest. He brought his face close to Angus. “Send me back!”

Angus moved his lips, then again. “I—I can't Wayland. I just ...”

Wayland's hand shot out, landed on the fireplace tools under the mantle where the photograph stood. “You stole her from me! You stole the years I would have had with her! You stole my life!”

He brought the iron poker down, once, twice, again and again. By the time he dropped it, Angus was not recognizable, and he was dead.

Wayland staggered back, his breath raw and hard. He put a hand out to steady himself, and there was a crash.

On the floor. The photograph, the glass over it broken.

He reached for it by his foot. A splinter of glass sliced his thumb, but he barely noticed.

The photo. The three of them, the others, the entire team.

He looked at Vera's face. It was wrong. It was too young, too fresh. She didn't look like the Vera he loved. Then again, the shaggy-haired young man who was barely older than he was didn't look like him, either, and Angus, he was a different person then, too.

When he placed the frame back on the mantle, careful to make sure it would stand without falling again, there was a stain on the face of the man he used to be, or never was. His own bloody thumbprint, covering that unshaven mess.

* * *

The investigation uncovered no motive, but the DNA and fingerprint evidence was clear. It was big news when the celebrated author, this college town's favorite son, was arrested for the murder of the great scientist with whom his life had been intertwined for thirty years. All over the news.

Wayland waited a day or two, until the press and police had dissipated, then he pulled up in the car he'd retrieved from the mall parking lot. He rang the bell.

The girl, Eudora, answered, face puffed from crying, but she narrowed her eyes, not certain she recognized him. Another reporter? “Do I know you?”

Wayland reached out, took her hand. “Don't worry,” he said. “I'm here to take care of you now.”

And he stepped into his house and closed his door.