Target with Four Faces

by

Garrett Rowlan

previous next

Hand-Me-Down

The Emerging

Days

Man

Target with Four Faces

by

Garrett Rowlan

previous

Hand-Me-Down

Days

next

The Emerging

Man

Target with Four Faces

by

Garrett Rowlan

previous next

Hand-Me-Down

The Emerging

Days

Man

previous

Hand-Me-Down

Days

next

The Emerging

Man

Target with Four Faces

by Garrett Rowlan

Target with Four Faces

by Garrett Rowlan

1

Night: Perez walked through lazy, luminous drizzle, rendered by streetlights into slow falling points. To either side of him, through the shut windows of houses and apartments, flickering TVs pulsed like buried hearts.

He passed the wet hoods of parked cars. One was occupied. It was a black car with a woman sitting in the front seat. Her eyes cut to him. Her glance was vengeful, he thought, looking away. Behind her, rain swept down a gutter.

He felt her eyes follow him. She hates but she doesn’t know me. But then he felt she did know him, somehow. In onehundred yards, the street dead-ended. He looked back. The black car had gone. He had not heard the engine.

Climbing a chain-link fence, Perez made only the slightest rattle. On the other side, he took the bag and ascended a narrow, wet, slippery hillside. Eventually, he reached a point where city lights spread below in a concentric pattern, crosshatched at intersections. Here, however, it was quiet and dark. Fifty feet up, he vaulted a second fence, and beyond he saw the house.

He had some misgivings. He had liked the Washingtons. This was just business, he told himself. Just like they had let him go four weeks ago; that was business too.

They had praised his efficiency and discretion, frowned on those qualities when applied to the way money disappeared in his presence. “I’m not a thief,” Perez said, when they gave him his notice.

“Then what are you?” Jonah Washington had asked. Jonah’s glance scrutinized. Getting no answer, he looked away. “It was always a temporary position,” he said. He stroked and smoothed the red silk robe he wore. “Other than that, Carol is sufficient for our needs.”

“I bet she is.” Perez knew the favors she had granted her employer. He knew because she had granted them to him, too. The phone rang, and Perez had used the opportunity of Jonah’s diverted attention to reach down and pocket two quarters on the desktop. He left the room, packed, and left.

Now, two weeks later, he returned, carrying a black bag. He passed the swimming pool, its surface twitching in the drizzle. Reaching the back door, away from the security light, he used a screwdriver to pop the wire screen with its two connecting hasps. The loosened screen sagged outward. He pushed it upward, buckling the frame enough to stick his hand under the sash and loosen the bottom jalousie slat from its flange. The opened aperture was wide enough to stick his arm in, up to the elbow, and flip the bolt lock. He opened the door. He had almost warned the Washingtons regarding the penetrability of this side of the house, but he had decided against it.

Waving his flashlight, he passed through the back porch and into the kitchen. Lightning flashed close, illuminating the sink and stove and the breakfast nook with its bay windows. The wine cellar was to his right. A sound came from there. A rat, perhaps, but whether with four legs or two, he didn’t know. “Hello?” His whisper chased his penlight down worn steps. He reminded himself that the rheumatic house often creaked, and that Carol was out with the Washingtons, driving them to dinner at the agreed-upon hour. Or so she had said.

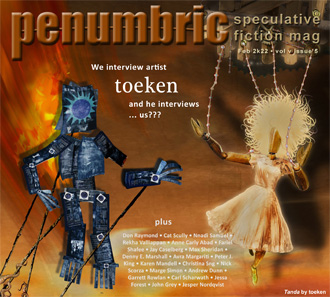

He turned down the hallway. To his left was the large, framed reproduction that occupied one wall, a target of alternate blue and yellow rings with four faces, or partial faces—only the chin, mouth, and nose visible—above. The wide, severe mouths and the occluded eyes reminded him of certain judges he had stood before.

“Jasper Johns,” Mildred Washington had told him, identifying the artist. “The original is worth millions.”

Perez didn’t see how. It gave him the creeps, perhaps because it reminded him of the feeling of being a target himself, right now.

Turning, he went down the short hall that led into the front room where the walls were high, the carpet was thick, and the Diebold safe waited. A couple of wall sconces were still on, creating arcs of illumination, one across a painting of Mrs. Washington, the house’s owner. A handsome woman in her fifties, wheelchair-bound, she was depicted wearing a gray serge dress and a checkered coat and holding a rifle at present arms. Her stern expression resembled her look when he’d driven her to the shooting range two months ago.

“How many shots do you see?” she asked, when he retrieved the target and gave it to her. She waited in her wheelchair.

“Four,” Perez said.

She shook her head, hard notches forming at the edges of her thin mouth. “It’s only one shot, the one that hit the center.” She tapped the bullet hole. “That’s the only one that counts. The others are only imperfections.”

“Only the bull’s eye counts,” he’d said. “Only the bull’s eye is real, is that what you mean?”

“Blank,” she said.

“What?”

“The center of the target is called a blank ... in archery, that is.” She leaned forward. “I like the idea. One shot with four phases, and the one that hits the blank is perfection, an artistry refined to its essence, which is zero, the center.” Her finger rested on the punctured paper with a delicate ease like a lover’s skin.

Waving the flashlight, the gun in his pocket, his gaze returned to the painting in which her eyes looked slightly to the left, as if in warning.

A light came on. Perez turned. Thickset, silver-haired Jonah Washington, his gun pointed, entered the room.

“Here you are, Mr. Perez,” he said, stepping forward. “Just in time to find me a widower.”

He fired. Perez managed a few steps down the hall—some vague notion of escape—before he collapsed close to the Jasper Johns. Lying on his back, Perez turned away from Jonah’s expression, which was sympathetic, and looked at the picture. Jonah followed his gaze.

“Which of the four faces is you?” Jonah asked. He got no answer. He didn’t expect one.

2.

Carol entered the hallway. “It’s done,” Jonah said.

“We got a problem,” Carol said.

“What?”

“He can’t shoot her dead when she’s already dead.”

“What do you mean?”

“I heard the footsteps and I heard Perez fall and when I looked over at her, she was slumped over. Heart attack? Or maybe we put the gag too tight.”

“Jesus Christ,” he said, “you dumb fucking hillbilly.”

Carol looked at him, choked down her loathing, reminded herself that it was all for the money and the property in that calculated future when she was Jonah’s widow, when she would have possession, when she would know, finally, that her life was not simply a passive series of phases; that her existence had not been a palimpsest of poses, layered incarnations that had happened to her, all beginning in that trailer park with her mother.

She glanced at the Johns painting. She had never liked it: creepy, and more so now. It was telling her, somehow, in its circles and half-hidden faces, that she would always belong to the outermost ring, the edges of things. And Jonah’s expression, the frown on his lips, seemed to push her out of his life, his promise to marry her already forgotten. She would never get the chance to be his widow.

“We’ll shoot her,” Jonah said. He made a vague gesture, as if that would clear him after the autopsy. “And when the police arrive, what are you going to tell them?”

He looked at her as if he were looking at an idiot.

“The burglar shot Mrs. Washington,” she said.

3.

Mollified, Jonah pointed at the basement, where Mrs. Washington waited with her wrists bound.

“Go fetch her,” Jonah said, holstering the gun. As she left, Jonah reached down and touched Perez’s face. He looked, really looked, at Perez, as if only in the stillness of death did that face disclose a secret, something that revealed more than Perez’s ironic expression of servitude. His lips were on the verge of opening and speaking something important, something that would explain the perpetual, wry set of his servant’s visage; but Perez said nothing.

What did Mildred say? One of her frequent grim observations. The truth was at the center, the blank. The truth was nothing.

He looked down. He felt as if he knew Perez from somewhere and their relationship was considerably different from that of master and servant. The same people but their relation expanded, somehow, into other strata of lives only half-glimpsed ...

Like the night Perez had died, Jonah recalled. It was another Perez, another death. Opening the door, Jonah had kissed him.

“Be careful,” Jonah said. He remembered how he had felt, embracing Perez inside that house, his home in another life, a place vague yet vivid, a ghost house. “She’s crazy.”

“It’s why I married her.” Perez had touched the gun in his pocket. “She keeps me on my toes.”

Jonah remembered closing the door and hearing the sound of Perez’s footsteps on wet pavement, just before the shot. Jonah ran outside. Perez lay on his side, still holding the pistol he had fired. In the street, Mildred, or someone like her, reclined coffin-ready, on her back, arms at her side, the gun in her right hand.

But that was crazy ... she hadn’t been paralyzed in a shootout. What had Mildred said about the bullet that had shattered her spine? “It was a hunting accident,” she had maintained, though she had never been an outdoors type, except for having Carol wheel her around the neighborhood.

For comfort, he thought of the house, only now the estate’s circular boundaries made him feel as if the grounds and the house at their center were part of a series of concentric spheres. Their space oppressed him; the farther they went out, the deeper he felt in the bulls’ eye, the blank.

Thoughts of Carol did not help. “We get married, right,” she said. Murder as barter, almost as if it were something she knew from before. She had hard eyes, like someone haggling. “Married as soon as we can. Otherwise ...”

“Otherwise?” he’d said.

“I might get my story mixed up.”

He’d deal with her later, deal with her and get free of her threats, not to mention her grammatical dissonance, her cigarettes, her Missouri accent stripped of its music by the California sun. And there was her possible treachery. She could be untying Mildred now. There had always been a suspicious undercurrent to their relationship, a wobble in the line that separated mistress and servant. They could have cooked up a deal. Mildred always thought one step ahead. She was clever; he gave her credit there. He almost wished she could be here when the cops came. She would be useful in the matter of her own murder.

They had shared a life together, one whose reality she questioned. “Where do our thoughts come from, Jonah?” She had wheeled toward the breakfast table, the way they had done for years: conversations over coffee, though in fact he had no concrete memory of those times, only partial memories imbricated like facing mirrors.

“I don’t know,” he said.

“I feel ... as if our thoughts are thought for us, as if I don’t want what I really want, but am expected to want.”

“And who does the expecting?”

“As you know,” her expression grew coy, “I’ve done a bit of writing. When you put down multiple drafts of a story you create characters that you change, you change their past to suit the plot. And maybe you suit yourself. You become them. That’s how I feel. I feel we are being written, Jonah. We’re characters.”

“You’re losing me there.”

“Don’t you ever feel that we were different people at different times and places?”

Just then he heard a sound from below. It sounded like something breaking.

“Carol?” he asked.

From down the curving hall he heard the sound of the wheelchair turning. He heard the squeak of one obstinate gear. The long shadow of a seated person flowed into the hallway and stopped at his feet. At first, the shadow had no source, but when he blinked he saw Mildred there, holding the gun on him.

4.

As Carol walked up the basement steps, Mildred Washington moved her arms and shoulders but not her lifeless legs. There was a knife she remembered in a drawer. She managed to open it and take the knife and with a right finger strong from pulling a trigger managed to hold the knife firm enough to saw her left hand free and with that hand take the dull knife and rub enough to slice the right hand free just as the overhead footsteps came her way. She put the knife aside. It would make things messy, and so she pulled a bottle from the wine rack. A glance at its label showed a supermarket-purchased brand, sufficient in terms of heft and expendable in terms of price.

Carol returned, opening the door above and walking slowly down the dark stairs. “Go fetch,” she muttered to herself, “like I was some kind of dog.”

When the girl reached the bottom of the stairs, Mildred reached up and swung, stunned the girl. A second blow cracked bottle and head. Carol slumped.

The girl was not educated, Mildred reflected, bringing the bottle a third and final time on her head, but she wasn’t stupid, either. She was like all of us, caught in concentric circles, surrounding a blank.

As the blood pooled, she took the service elevator upstairs, and as she rolled down the hall, she noticed that each turn of the wheel was facilitated by a swath of resistant space that fell into black, as if it were being highlighted before deletion. Her hand steadied the gun, aimed at his gut for maximum impact. It produced in Jonah a confessional mood.

“I apologize,” he said. With Perez crumpled at his feet, she didn’t know who he was apologizing to. “I haven’t been the best husband in some ways. I caused problems in my marriage.”

She made a mitigating gesture with the gun, a shrug in steel. “Well, what marriage doesn’t have its ups and downs?”

“Carol’s just a servant. It really doesn’t mean anything.”

“She was your lover.”

“I’d call that a euphemism,” he said. “An element of romance to describe something that was rather sordid. It meant nothing.”

“Oh, honestly!” she said, pulling the trigger.

She rolled forward, stopping beside the two fallen bodies. She looked up at the painting. She saw the frowning mouths not as visages of evil. Rather, the incomplete faces suggested things poorly done, like drafts of stories that never mesh, drafts written to escape the inward suck of emptiness, of blankness. It was happening now. Already she felt that the house had disappeared except for its essentials, the hallway and the hanging picture. She looked at its four faces and then turned the wheelchair around so that the shot, if her logistics were right, would exit the back of her head and enter the wall in the center of the target. She opened her mouth and looked up into sky-less black. As she pulled the trigger, the blackness rushed toward her, the world imploding, all space vanishing as it narrowed to a single point, a last burst of light, and a blank.